A knitted banner that says “Stronger Together” stretches over the steps on the front porch of the Kennedy Heights Arts Center (KHAC). With its quirky multicolor letters, pompoms, and flowers crafted by members of the BombShells of Cincinnati, it’s a rallying cry for collaboration, and a fitting introduction to the Center’s current show, “Collective Impact: Females Joining Forces”.

BombShells of Cincinnati, “Stronger Together”

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

The sign brightly broadcasts a resonant welcome back to people timidly emerging from the long pandemic winter. Inside the building is a series of installations from seven Cincinnati-based female artist collectives: Art For Artists, ART HAGS, BombShells of Cincinnati, LOOK, Maidens of the Cosmic Body Running, PhotograpHERS, and Pull Club. To extend the context in a global capacity, wall labels mounted in the side gallery provide information about other historic and current collectives of women working around the world.

The history of the female artist collective as a movement is difficult to trace and remains a category for deeper research. Since the late 1800’s artists have collaborated to provide a context for themes and perspectives that exist outside of mainstream art commerce and commonly acceptable tastes. Throughout evolving 20th Century art movements, various groups organized and exhibited together based on common theoretical foundations, such as the Dadaists and Surrealists, Situationists International, and Fluxus, but were still based on the individual artist producing individual works. These groups included few, if any, women.

Social and political activism of the Civil Rights, Anti-War, and Women’s Movements of the 1960’s became increasingly intertwined with art movements. At the time, the New Left, a philosophical and political movement based on a reinterpretation of Marxism, was a major influence with university students and activist organizations of all kinds. The idea of collectivization originates with Marxist ideology and prioritizes the collective actions of community workers over the autonomous role of the individual. Groups such as the Art Workers Coalition formed in New York City to demand greater rights and equal conditions for people of color and women in the arts. Subsequently, groups like Women Artists in Revolution (W.A.R.) in 1969 and later the Guerilla Girls in 1985 organized in order to refute the idea of the individual artist “genius” (a.k.a. a white male) that often excluded them in the gallery and museum system, in favor of collective ideas and action that made space for new ways of approaching art and its power to impact society. Today, collective strategies continue to be explored in the works of artist groups both locally and globally.

BombShells of Cincinnati, BombShells Manifesto and Mannequin Heads

Photo by Susan Byrnes

“Collective Impact: Females Joining Forces” provides something many people have missed for an entire year – a sense of community, and the timing of the show couldn’t be better. As people begin to gather together again, the projects illustrate what it means to be a part of a community, and what a collective focus can bring to issues of concern and creativity. The BombShells, whose installation occupies the first of several rooms in the KHAC, don’t mince words here. Over the fireplace hangs their “BombShells Manifesto”, mounted on a panel with a knitted frame, with statements like, “We aim to soften the edges of an otherwise cruel, harsh environment”, “We are actively contributing to a more positive type of global warming”, and “If you don’t like it, just unpick it,” reflecting the nature of their “yarnbombing” artwork, which they refer to as a form of removable graffiti. Beneath the frame rests five mannequin heads on the mantle, donning dark sunglasses and blonde wigs, with colorful knitting stretched over their faces to indicate their anonymity.

The artist manifesto, a public declaration of beliefs, has long been a fixture among 20th Century radical art and political movements and collectives, from the 1909 Italian Futurist manifesto to the many statements and slogans distributed as posters, print ads and billboards by the Guerilla Girls, who anonymously protest underrepresentation of women in the art world. Still active, they wear gorilla masks to protect their identity, while adopting names of deceased female artists. For them, a collective not based on individual identity and authorship made sense because women artists faced real retribution for demanding change from the museum and gallery system, run primarily by white males. Their street-art and protest-oriented tactics have influenced the work of many artist collectives, clearly including the BombShells.

Pull Club, “Your Casual Racism Kills”

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

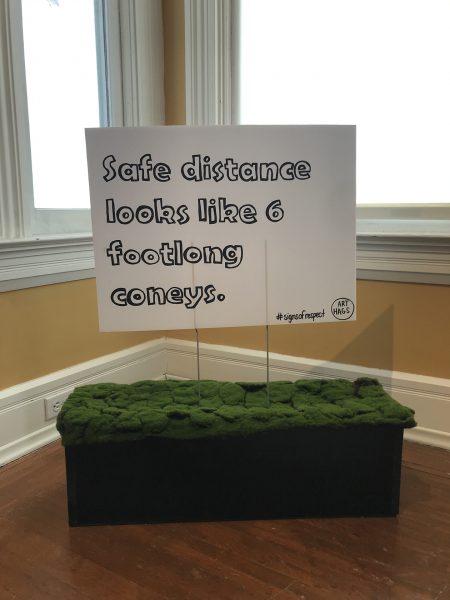

ART HAGS, “Signs of Respect”

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

Anonymity is also a feature of the poster and protest sign, because their messages rarely reveal an author. Instead, through text and graphics they project an authoritative voice with an urgent message for whomever is willing to receive it. Printing is an inexpensive mass produced mode of public political expression and is a simple vehicle to make a message broadly visible and accessible. These concepts influence the methods that have been adopted by the ART HAGS and Pull Club. Graphic works by the Pull Club, a screen printing and design cooperative, are installed on billboard structures that follow the KHAC’s circular driveway, so visitors can view the works from their car or by strolling outside the building. Images with slogans, such as a pink flowered sign that says, “Your Casual Racism Kills”, underscore issues like social justice, sexism, and climate change.

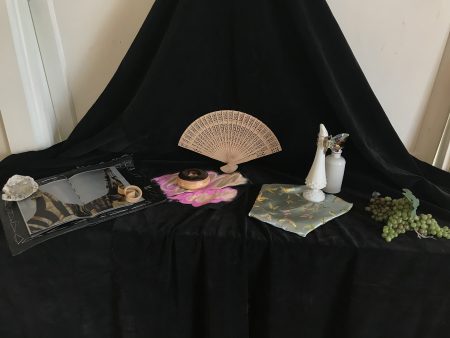

ART HAGS created the 2020 project “Signs of Respect” as a response to COVID. These hand-drawn plastic lawn signs, produced in mass, humorously encourage masking and social distancing. Extra signs were created for the exhibition which visitors are invited to take home. The collective, which refers to itself as “a coven, or a group of friends”, convene to create space for their artwork and for the acknowledgement of women in the arts, as in their piece “Holding Space: The Jeanne Claude Project” that references the contribution of Christo’s partner Jeanne Claude in the creation of The Gates installation in Central Park. The duo LOOK works in poetry, performance and printed matter, creating work about friendship, cultural lines, and comedy as therapy. Their quiet installation consists of a series of printed poems and two object arrangements that contain seemingly symbolic things with cryptic meanings, like the ceramic chocolate glazed donut and plastic butterfly hair clip in the piece “Bermuda Altar.”

LOOK, “Bermuda Altar” Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

Maidens of the Cosmic Body Running, “Promise of Green”, detail

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

Maidens of the Cosmic Body Running, “Promise of Green”, detail

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

Maidens of the Cosmic Body Running create yet another kind of space for this exhibition. The three-member group makes video installations and animations. Their piece “Promise of Green” presents a space for relaxation and meditation. Rest is a recurring theme in their work, as are triangles, here present in the shape of a large shag rug on which viewers are invited to sit to look into a round mirror overlayed with a pattern of triangles. Onto this is projected a blurry video of a single bright green shoot emerging from a seed in the ground. The work is inspired by the history of Lewis Kennedy, for whom Kennedy Heights is named, whose father-in-law was known as a seed salesman. The visually mesmerizing work is characteristic of much of their output, which centers on, as their website says, “the power of the photographic image as a vehicle for romance”.

Pat Timm of PhotograpHERS, “250 years.”

Photo by Pat Timm

Work from the group PhotograpHERS views the world through a somewhat less romantic lens. Typically working as a group of individual artists, for this exhibition they reinforced the collaborative process by digging into their experience of being women artists during the pandemic. Over many Zoom meetings they discussed issues of oppression and wage inequality for women in the workplace that were affecting them directly, as the resulting photographs illustrate, such as Pat Timm’s image “250 years. It will take over 250 years, at the present rate, to close gender pay gap.”

Art for Artists, “The Walk” Installation

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

“The Walk” detail of Rachel Carson shoes by Arnelle Dow

Photo courtesy of Kennedy Heights Arts Center

Art for Artists is a group that convenes at the Dunham Recreation Center on the West Side. It’s a large and fluid group of artists who create projects comprised of individual contributions to group themes, as opposed to an installation with a singular, cohesive style. Their component-oriented approach to collective projects worked perfectly for the installation titled “The Walk”. Consisting of 27 pairs of embellished shoes, the piece walks viewers through a history of prominent, influential, and otherwise beloved women, including the outspoken journalist Ida B. Wells, environmental activist and writer Rachel Carson, and politician and activist Stacey Abrams. Installed in a spiral, the way in which the shoes were revised and decorated to show something about each person kept me looking for a long time. The piece recalls the mail-art “100 Boots” postcard series by Eleanor Antin. From 1971-1973 Antin posed and photographed 100 pairs of identical black rubber boots as if they were marching through urban and rural landscapes. Like Antin’s boots in formation, the shoes in “The Walk”, take on an anthropomorphic personality, with a group gesture that feels intimately human.

While each of the groups in this exhibition has a different basis for their interactions, there are common themes that connect across the collectives. Many of the groups have fiber art in the show or have members who identify as fiber artists, which promotes a dialogue about craft forms and their relevance as art and subverts a false dichotomy that often denigrates traditional women’s artforms like knitting, weaving, and sewing. Most of the groups create work that has an overt social or political message, addressing topics such as gender inequity, racism, environmental issues or human rights. A number of these groups create work intended to be seen outside of the traditional art gallery setting, which is well represented in curator Mallory Feltz’s choice to use KHAC’s indoor and outdoor space for the exhibition. Several works pay homage to other women or women artists in an attempt to keep their efforts, struggles, and contributions from being erased from history. This inspiring exhibition itself serves as an important effort in that regard.

–Susan Byrnes