Kent Krugh is a long-time contributor to the Ohio art scene, bringing a sophisticated historical sensibility to his work as a photographer and curator. After taking physics degrees from Ohio Northern University and the University of Cincinnati, he spent forty years developing his camera craft, winning a range of accolades including a gold medal at the Tokyo Foto Awards. He has held shows in Argentina, Colombia, Guatemala, and Poland, as well as celebrated venues across the U.S., all while remaining a formidable creative presence in the Greater Cincinnati area. In 2018, he curated New World: Refugees and Immigrants Photograph the Experience of New Life in America, which appeared at the University of Cincinnati Clermont campus as part of the FotoFocus Biennial festival. And in 2021, his curatorial savvy is on display once more at the Off Ludlow Gallery, where he has arranged his photographs into a travelogue called Under the Influence: Beauty and the Surreal in France.

The show gathers black-and-white and color photographs of Krugh’s first trip to France, which included stops in Arles, Goults, Roussillon, L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, Mont Ventoux, and Paris, among other places. The compilation accentuates his talents as a photographer of landscapes and fine architecture, though its richest insights derive from Krugh’s engagement with the history and aesthetics of surrealism. Many of the principles, or, better yet, anti-conventions of that movement emerged in France after World War I, and their influence continues to take shape a century later. As André Breton conceptualized surrealism, it took issue with philosophical insistence on logical development, preferring instead to generate incongruous juxtapositions and linger in ambiguity. It expressed strong suspicion of ideologies of progress, whether in the flow of argumentation or the history of social relations, favoring unruly assemblages and uncanny dream-images instead. And by contrast to art that focused on distinguished people, events, and objects, surrealism reoriented “the power of thought towards apparently trivial or inadmissible subjects” (Fijalkowski and Richardson 10). Like Breton and other surrealist ancestors, Krugh regards assessments of triviality or inadmissibility as provocations rather than conclusions.

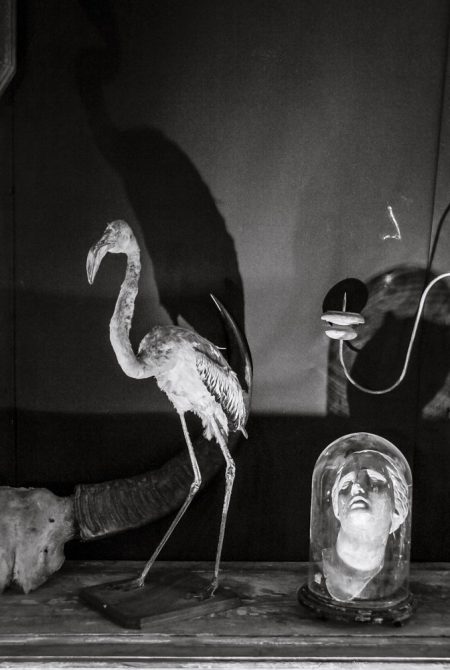

His feeling for the poetry of seemingly inconsequential things expresses itself most plainly in Antiques at L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue Market. Rarely has a stuffed flamingo looked so threatening, and rarely has it presumed to govern such a weird array of subjects. The bird takes on a monstrous character in the hard glow, casting a hunched, vampiric shadow against the back wall. A sculpted visage suffers under glass as a beaver tries to sneak offstage, all while a crowd of trinkets watches from the wings. The mise-en-scène thus displays how readily knowable, nameable things relinquish their standard meanings when thrown together in novel ways. But even as it provides a catalyst for playful storytelling, it also rejects the comforts of narrative: instead of resting easy with figural or symbolic meanings, the image prompts consideration of the abstract, affective, and serenely bizarre dimensions of its miniature world. The picture rewards a Keatsian negative capability, nudging us to dwell in the excitement and dread that uncertainty brings.

Antiques at L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue Market,

Kent Krugh

Krugh’s Flattened Bottle at L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue Market continues that paradoxical story about how surreal photos refuse to be stories while their arguments rebuff argumentation. The outline of the bottle yields a frame-within-a frame, which emphasizes the mechanics of the creative act while prompting reflection on the selectivity of vision. Disrupting the everyday use of the object and denaturalizing its curve, the picture draws our focus to where the label should be. In place of a brand, we find figures lifting the wings of an early airplane as a child crawls along the lower plank. The drama evokes fantasies of travel as it unfolds atop the markings of a faded map. Light falls brightest across the depiction of human action, darkening at the bottleneck where the action empties out. But as with Krugh’s other market photo, mimesis retreats before the materiality of the object, which extends to the makeshift stand and the glassy curios in the background. While the show suggests an artist “under the influence” of beauty, it also a connotes a fascination with haptic experience, and with the life of things beyond utility and the profit motive. As such insights accompany a trip to the market, a subtle irony emerges: although the objects are presumably for sale, they also try to occupy an economy outside the financial.

Flattened Bottle at L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue Market,

Kent Krugh

Tango Dancers at the Theatre Antique,

Kent Krugh

As Krugh celebrates those forms of material culture that defy commodification, he similarly honors forms of human experience whose value exists in bursts of pleasure, perception, and physical intensity. Tango Dancers at the Theatre Antique conveys the joy of motion, capturing in still photography the energy of twisting legs, whipping hair, and bodies snapping into place. Intricate, rapid-fire stepping coexists with the fluid rhythms of approach and retreat; swirls and plunges give way to poses at once sensual and severe. The image recalls Cubist painting by combining multiple views of a focal object in a single mosaic. But there is also the surreal oddity of free-floating appendages, transparent limbs, bodies impossibly merged, the front and back of a dancer’s head shown in the same space, furniture and torsos blending into each other, glowing footprints marking where the dancers have been.

Plane Trees Along Road to Arles,

Kent Krugh

Krugh’s landscapes and village scenes engage less obviously with surrealist aesthetics, though they still fit nicely with the rest of the show. Plane Trees Along Road to Arles displays the linearity and order Breton rails against while also subverting those conditions. It impresses us at first with its symmetry: a procession of trees with echoing trunks and forks, hugging a country road in a smooth flow from lower left to middle right of the picture plane. Painted stripes on the road reinforce the gradual upward glide. We experience a darkening as the eye moves from left to right, starting in small ways with the individual trees and then coming to characterize the whole composition. A house sits just off the road, peacefully positioned amid the regular geometry. But there are also moments of dissonance as boughs break off abruptly into other, misaligned branches, the leafy canopy fragments in unnatural ways, razor-straight splices appear in mid-air, and pictures-within-pictures disturb the calm. The sutures within the image prompt us to think of natural order as a conventional expectation rather than a given. They also produce a certain irony, as strips of superimposed scenery interrupt the picture’s smooth linearity with yet more lines. The resulting arrangement once more recalls Cubism by appearing to unfold objects onto a flat plane where everything collides. As layers from mismatched stills become increasingly apparent, what looks at first picturesque takes on the quality of a flickering film projection.

Rousillon,

Kent Krugh

An even more striking remediation of nature photography occurs in Krugh’s Rousillon. The 30’ by 52’ archival pigment print affords an aerial view of an antique mountain town, and then gently reveals itself as a visual pun on the idea of organic architecture. The buildings blend so smoothly with the crags that they seem to spring from the ground, partnering with the dense greenery rather than displacing it. But staying with the photograph means encountering uncanny doublings and refusals of gravity, and gradually recognizing the sort of superimpositions that also characterize Plane Trees. The houses drift up the mountainside and finally rise into the sky without any need for foundation, branches breaking the frame into emptiness. Pushing the organic metaphor past its limit, the photograph fuses the sublime and the comical.

Not only does Krugh parody organicism, however. The whole show seems set on troubling the idea of nature. It insists on the life of things beyond human perception and appropriation, coding the designation “natural” as an intrusion, an act of mediation that tries to erase itself. This sensibility exists quietly in shots that give mountain brush the look of crushed velvet, and more obviously in Krugh’s self-conscious attention to framing, layering, and tinting. His project of denaturalizing the visible tends to throw off conventional hierarchies of value, deconstructing the icon while raising up the supposedly trivial and inadmissible. Near a desaturated, meticulously pixelated Paris skyline we find a photograph of blue and red posts curling down a hillside, clashing wonderfully with the earth tones that surround them. Together those posts mark out a pathway. And though that pathway reiterates the show’s emphasis on travel, it bursts the confines of symbolism and offers nothing so straightforward as progress.

–Christopher Carter

Works Cited

Fijalkowski, Krzysztof, and Michael Richardson, eds. Surrealism: Key Concepts. Routledge, 2016.