A Monumental Collection: Perspectives from the David C. Driskell Center

By Christopher Hoeting

Only when we recognize the historical patterns of isolation and accept the responsibility of supporting those artists who express themselves in a universal language of form will black American artists be seen as major contributors to the art of this century.

– David C. Driskell

On February 15, 2013, the Cincinnati’s The Taft Museum of Art introduced a traveling exhibition to the region: African American Art Since 1950: Perspectives from the David C. Driskell Center. Through a variety of media, the exhibition presents over sixty works by fifty-four artists who have expanded the field of African American art over the last six decades.

On Thursday March 21, the Taft Museum will host distinguished speaker David C. Driskell: Career, Collecting, Collection: David C. Driskell in His Own Words. Driskell’s talk inside the house of another monumental American art collection is the perfect occasion to experience this important exhibition. Driskell’s life and collection—seamlessly intertwined—provides an entry point into the study of African American art. During a conversation at the University of Maryland, Driskell told fellow artist Richard Klank, “I make art to free myself, to give a new dimension to life, and hopefully to other people’s lives…. I went back to nature and relied very heavily on my natural environment as the source of inspiration in my work…. Part of the message that I desire to communicate in my art is that I am a Black American. I have experienced the haunting shadow of an African past without knowing its full richness…. I wear the badge of a proud and ancient culture in my black skin. But my art is heavily imbued with Western forms” (Contemporary Black Biography, by the Gale Group, Inc).

As an artist and teacher, Dr. David C. Driskell has written about, curated, and collected more than 100 artworks permanently loaned to the Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, a center committed to collecting, documenting, and presenting African American art. Driskell’s collection has helped to enrich the conversation of African American art and preserve the rich heritage of African American visual art and culture. As artists and collectors have donated to the collection (it has grown ten fold over the last decade), it is one of the most important African American art collections in the country.

The traveling exhibition now on display at The Taft Museum is co-curated by Driskell Center Director Dr. Robert E. Steele, Deputy Director Dorit Yaron, and independent scholar Dr. Adiennee L. Childs. In the exhibition catalogue, Dr. Steele revealed that the exhibit is “not intended to be an all-inclusive and/or comprehensive exhibition that highlights all important artists and movements, but rather, as the title indicates, to provide a perspective from the David C. Driskell Center by presenting works from the Center’s permanent collection… Also included are a few works on loan by artists which we felt were important to include and whose works we hope to have in our collection.” (Steele 3)

In the catalogue, Steele states that the exhibit “explores three thematic ideas: (a) the David C. Driskell circle, his contemporaries, collaborators and students; (b) the personal and the political; and (c) new voices.” (Steele 3) The exhibition begins with several pieces from the original Driskell collection and highlights his mentors and colleagues (which includes works by Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Elizabeth Catlett).

Two tremendous works prominently displayed in the first room of the exhibition by Elizabeth Catlett stand out: The Black Woman Speaks (1970) and Gossip (2005). The Black Woman Speaks is a large wood sculpture: a wonderful, simply modeled head of a female figure with imploring painted eyes. The artwork is made out of smoothly sanded and beautifully coated dark polychrome wood. The overall gesture of the head is tilted slightly up and back. With eyes wide open and mouth ajar (a seemingly hopeful (?) gesture), The Black Woman Speaks imbues the viewer with tension; as the viewer, I earnestly await hearing the voice of the powerfully sculpted figure.

The second work made years later, Gossip, is a lithograph highlighting a shared affinity between two young women. This excellent print, which carries a similar simplification of form that the artist achieved in The Black Woman Speaks, reveals this analogous effect in two rather than three dimensions. Due to the modeling of light and the use of value, the combination of volumetric form on the figure is reminiscent of Catlett’s contemporaries, such as Pablo Picasso and Fernand Leger. Catlett’s image uses color in subtle ways to highlight the use of value as a light source on both the dark skin tones and on the shirts of the women. By contrast, the background consists of red horizontal stripes and breaks up the overall design to create movement, establishing a ground plane upon which each of the figure’s arms rest. Gossip is an intimate look at two sincere friends huddled together in a close conversation. It is an excellent depiction of the human experience—made with a closeness and ease that is approachable; Gossip is thus universal.

The voices of woman are heard throughout the exhibition/collection. As you enter the next two rooms in the gallery, artists Stephanie Pogue and Margo Humphrey are represented (each of whom were colleagues with Driskell at The University of Maryland). Pogue’s piece, Dancing Goddess, uses the female form to explore figuration with an exquisite color palette. The symmetrical composition highlights two figures locked at the hip and suggests a rhythm of repetitive patterns flowing between each dancer. The brightly colored yet flat red background creates a silhouette of the women; the forms highlight the shape and the beauty of the female torso, a shape and form similar to the female figure represented in fertility sculptures.

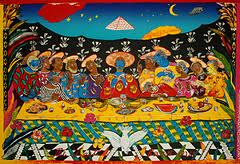

Margo Humphrey’s The Last Bar-B-Que, a self-described “reinterpretation of Leonardo di Vinci’s The Last Supper,” is a complex lithograph in both technique and content. Humphrey’s portrayal of the last supper is a meal shared among women and men alike. Creating an ethnically diverse representation of figures, Humphrey serves dishes that are stereotypically African American as well as provisions conventionally biblical—an array that both diffuses and empowers the experience. The print is filled with complex colorations, patterning, and symbols. The focal point of the print is the Christ figure (with blue skin); upon viewing, the eye is next drawn downward to an inverted white dove and cursive words stating: The Last Bar-B-Que.

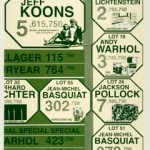

Turning the corner into the largest room of the exhibition, you are confronted by many works that focus on personal and political themes. I could not help but notice an artwork by Kerry James Marshall entitled May 15, 2001 R.I. Marshall’s silk-screen print is a green, monochromatic, grid-based composition with images of artist names, artworks, and sale prices taken from an auction held on May 15, 2001 at Sotheby’s in New York City. In this highly conceptually based work, Marshall uses the value (or rather the devaluing of Jean-Michel Basquiat, a well known African American painter) to point out the overt racial inequities in the market place.

In the corner of this large section of the exhibit, I am next drawn to what appears to be an anomaly in this eclectic exhibition: Untitled #4 (2006) from the series Suburbia by artist Shelia Pree Bright, a new voice in the collection.

Due to its open composition, the artwork appears among very few pure photographs and has a rather strange presence within an exhibition dominated by collage, printmaking, painting, and mixed media. In Bright’s photograph depicting a suburban still life, objects, shapes, and surfaces are examined and charged with stereotypical representations. “Miniature Brazilian Maracatu dolls, the Carew Rice Tumblers, and Jamaican Woman Salt Shakers” are all mundane items on a kitchen counter, shelf, and windowsill that, combined and ignored, become racially charged. In the photograph, Bright “uncovers the disturbing presence of these racist collectables in an African American home, calling into question the racial consciousness of the black middle class.” Even the less obvious kettle and honey containers have sizes and shapes that take on racial connotations.

The exhibition continues through two zigzagging rooms of a who’s who in the world of abstraction in African American art, including artists such as Martin Puryear, Felrith Hines, Sam Gilliam, Kevin Cole, Moe Brooker, and Alma Thomas. Along the last long wall of the exhibition is Chakaia Booker’s more recent piece (2010) entitled Four Twenty One. Booker is a rising talent who not only represents a new voice in the collection, but she also represents a woman making a universal statement in themes that both relate to African American art and to the world at large.

Booker’s mixed media piece, a collaboration between Booker and Curlee Raven Holton (Director of the Experimental Printmaking Institute at Lafayette College, Easton, PA.), is a layered print—a shift for Booker, who frequently works with assemblage of found objects and industrial materials (most notable her works that incorporate tire fragments). In contrast to her typical methods, in Four Twenty One, Booker creates a flat print on glass. I was surprised to learn that the multilayered imagery within the print is comprised of photographic negatives of tire sculptures created into screens and printed on the smooth, slick finish of glass. The abstract image uses graphic organic lines snaking around the composition (reminiscent of the brush stroke painting by Roy Lichtenstein); the chaos of the composition is balanced by the buried achromatic and interwoven grid structure.

The strong horizontal open space at the top and on the left side of the print offers a moment to breathe; yet when you notice the more grid-based relationships, your gaze topples, spiraling toward the center. Booker’s piece is a nice break from her signature work and as a new voice to an expanding collection from the Center.

Another compelling aspect of this exhibit is the pairing of the collector and the location—observing both the Driskell and the Taft Museum Collections side-by-side offers interesting insight into two very important private American collections. It invites the viewer to ask how collections initiate, take shape, become public, find a home, and are augmented. Further, by examining the collections themselves, we are afforded the opportunity to understand varied cultural, historical, and personal perspectives.

Interestingly (and by design) the Driskell Center Collection currently finds itself located in the same complex as a rare and significant piece of early African American art—the Robert S. Duncanson murals. These murals, located on the walls at the Taft Museum, create a voluminous foundation upon which to discover new perspectives in contemporary African American Art.