by Trish Richter

February 14 – March 14

Trailing behind the phenomenon of globalization is the individual’s growing awareness of its identity within a politically, socially, and environmentally global community. Old news, yes, but this concept is exponentially significant as the world continues to shift at the expense of both humans and the natural world. We have come to realize that our society expands beyond our local community to encompass the greater community of the more-than-human world, and as a collective existence we are presented with the duty to acknowledge this. This awareness presents us with an increasingly urgent responsibility to ourselves, to one another, and especially to our children to be active influences over our world’s social, political, and environmental future. I was struck by the very aware acceptance of this responsibility throughout my experience at Xavier University’s faculty exhibit, which included recent works in ceramics, fibers, paintings, photography, prints and sculpture by Suzanne Chouteau, Bruce Erikson, Jonathan Gibson, Marsha Karagheusian, Kelly Phelps, and adjunct faculty Chris Hoeting, Jordanne Renner, Dana Tindall, and Kitty Uetz.

Of the costs of hypermodernity, one of the more commonly discussed are the dehumanizing effects of working within the cogs of the proverbial machine of human progress. In their ceramic mixed media relief, John Henry, twin brothers Kelly and Kyle Phelps depict the struggle of the invisible worker. The American folk hero John Henry, a steel driver pitted in a race against a steam-powered hammer, is a symbol of human endurance against the impending threat of the machine age. Although Henry overcomes the machine, his visage and tale retain their significance because our man versus machine contention has all but ended. Caught within the mechanisms and toil of progress, the average worker continues to be dehumanized and exploited by our industrial growth based culture, locally and globally. This piece draws the viewer into the common experience of the average human. Although the machine we face is overwhelming, the Phelps brothers’ piece conveys the very real misery that is inherent within this system while retaining the hope found in John Henry’s tale.

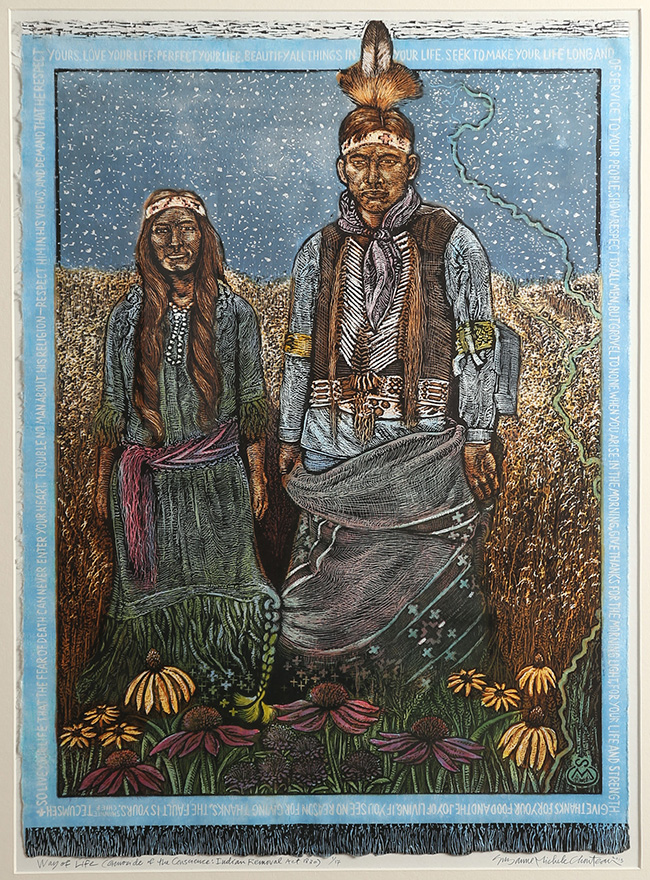

The focus shifts to the effects of our industrialized culture upon the natural world while telling a story of intergenerational ties in Suzanne Michele Chouteau’s series of woodcuts. In Way of Life, which depicts August Chouteau and Jane Bluejacket on their wedding day in Oklahoma territory, snow falls in the backdrop referencing the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and “the fact that the US government began the westward expulsion at the onset of winter resulting in thousands of human beings dying along the way.” The Indian grass before them alludes to the tall-grass prairies of their ancestral lands. The text of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh’s “Way of Life” borders the image like a pattern on a blanket:

So live your life that the fear of death can never enter your heart.

Trouble no man about his religion—respect him in his views, and demand that he respect yours.

Love your life; perfect your life. Beautify all things in your life. Seek to make your life long and of service to your people.

Show respect to all men, but grovel to none. When you arise in the morning, give thanks for the morning light, for your life and strength.

Give thanks for your food and for the joy of living. If you see no reason for giving thanks the fault is yours.

Suzanne Michele Chouteau. Way of Life (Genocide of the Conscience: Indian Removal Act 1830), Reduction woodcut; 22″ x 16″

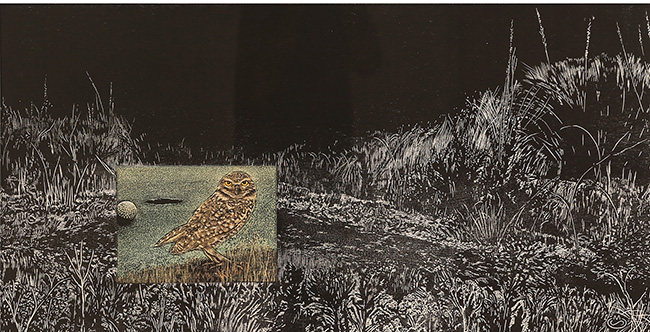

The ancestral land alluded to in this portrait, the North American Prairie ecosystem, once embraced the Native Americans. This coexistence with the animal and plant communities was lost with the persecution and slaughter of the Native Americans, with the land being subsequently “plowed, developed, overgrazed, and abused to the point that only fragmented remnants of the original grasslands remain.” In the two versions of North American Prairie (Engulfed), a reduction woodcut mounted on woodcut, an owl stands on the urbanized land of a golf course and stares intently and directly at the viewer. The developed space confined within this box is engulfed by the overlaid landscape of the once brilliant and now lost prairie lands.

Suzanne Michele Chouteau. North American Prairie (Engulfed) Reduction woodcut mounted on woodcut; 24″ x 46″

The final piece in Chouteau’s sequence of woodcuts, Beaver (Regeneration), captures the beaver in its natural habitat. Although beavers are second only to humans in their ability to alter a landscape, the nature of their influence over other life is vastly different from ours. Native Americans called the beaver the “sacred center” of the land because, in addition to creating a rich habitat for other wildlife, they purify water, maintain wetlands, alleviate droughts and floods, lessen erosion and raise the water table. In contrast to these life-sustaining dynamics, humans have so altered their role and influence over their ecosystem in the name of progress that the idea of existing in this sort of balance with the natural world seems almost unnatural to many of us. Nearly wiped out by the early 1900’s, the beaver population is thankfully regenerating.

This growing collective human consciousness as members of the more-than-human world promises more instances of regeneration. As the character of John Henry leaves us with the lingering hope of human potential and endurance, Marsha Karagheusian’s ceramic earthenware, These Birds Have Flown, presents us with a rusted bodice, reminiscent of the fertility goddess, whose countenance holds a proud contentment and tranquility. With her hands cradling an empty nest, adorned with the leavings and feathers of recently flown birds, this woman projects a love for fostering and cultivating the potential and promise of life. Her gesture is protective yet unrestrictive, a suggestion of an alternative, symbiotic relationship between humans and the natural world.

These imbalances and injustices exist not only within our relationship to the natural world but also to one another. Although much is required to trigger a shift in troublesome cultural paradigms, such as the patriarchal perception of female sexuality, the process begins as a ripple effect. A contributor to this process and teacher of figure painting and drawing, Bruce Erikson continues to examine mainly the voluptuous female form, adding hot, hot color to his luxuriating figures, and more than a touch of postmodern pastiche. As one of the best interpreters of the human form in this region, Erikson uses the most difficult of poses, from upper right to lower left, feet-to-face, in a reverse “S” curve of extraordinary difficulty. In Rapture, Erikson’s model, her jewelry, objects and color seem more Bollywood, exotic and multicultural, than Classical European as he expands our idea of beauty within his formalist languages.

And though Jonathon Gibson’s photographs are somewhat unclear in their meaning and intention, his often-conceptual photographs have a sociological and psychological edge to them, so that he captures an underlying unease, characteristic of our age of hypermodernity, in much of what he photographs. Both Erikson and Gibson seem to enjoy pushing their color into near Surrealism, and it’s reassuring to know that these two younger full-time Xavier University faculty members are continuing to experiment with their own work and adding significantly as teachers and artists to the discourse on contemporary art and the numerous issues it addresses.

As shown by these artists, we can be artisans of cultural change if only we chose to do so. To attain this, we must redesign our relationship with the world, from creating our own sustainable niche within the greater community as the beaver does to reevaluating our perception of beauty and the physical form of female sexuality. The artistic students of Xavier are in capable, talented, and intentional hands.

Trish Richter has a B.A. in comparative literature from the University of Cincinnati and is a freelance writer and a communications and public relations consultant.