by Karen Chambers

In “Under the Sun” (what a great title for an exhibition of photograms made by the sun), Anita Douthat is presenting four series — “Transparent Uniforms,” “Bridal Suite,” “Alterations,” and “Candelabras for Constantin (Brancusi)” — in a solo show at the Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Art Gallery.

Photograms were among the first photographic images made as 19th-century scientists and artists experimented to find how to create images (camera-less and in-camera), fix them to make them permanent, reduce exposure time from days to “mere” minutes, and replicate them. In other words, make photography practical.

A Cincinnati native, born in 1950, and now living in Alexandria, Douthat has been making photograms since 1980. Douthat, who now lives in Alexandria, explains her process as “using the sun as my light source and doors or window shades as my (camera) shutter, I produce photograms by placing objects on ultraviolet light-sensitive printing out paper.” Exposures take about five minutes, and Douthat does them between May and October, when the sun is strongest. After the exposure is made, she chemically gold-tones the sheet, which produces a rich array of colors, from reddish-brown to purple to blue-gray. The photogram is then fixed for permanence.

Douthat says, “The resulting exposures produce ghostly, negative silhouette-like traces . . . (They) capture an essence or suggestion of an object rather than a surface description.”

One of the key pioneers in inventing photography in the mid-19th century,1 William Henry Fox Talbot, called photograms “photogenic drawings.” He beautifully described them in his 1844 book, Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing:

The most transitory of things, a shadow, the proverbial emblem of all that is fleeting, may be fettered by the spells of our “natural magic,” and may be fixed forever in the position, which it seemed only destined for a single instant to occupy.

Douthat became enamored of the photogram technique as a grad student at the University of New Mexico in 1980. In her studio classes, she combined “photographs and photograms in color, an arduous process before the advent of the digital era.” Douthat’s M. F. A. dissertation was Tracing with Light: A Critical and Historical Investigation of the Photogram, giving her a solid foundation for her later work.

A couple of events confirmed Douthat’s dedication to the photogram. In 19882, she slipped on a wet curb in New York City, breaking her shoulder. A few months later, her mother was diagnosed with cancer. “So much for my sense of invincibility,” she recalls. “Suddenly the idea of working with shadows took on a much more personal significance.” What she calls “the presence of absence” became very important in her work.

In the ’90s, Douthat worked with inanimate objects such as anatomical diagrams, bone scans, glass bones, stools, empty chairs, a wheelchair, a sled, among other things, but there was always an implied human element. Garments are obviously stand-ins for the human body. Douthat selects them for their delicacy, which relates to the transitory nature of life. In essence, all of Douthat’s works are memento mori.

Another critic might interpret the photos as a dialectic about feminism and draw parallels with artists like Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, Marina Abramovic, Charlotte Moorman, and on and on and on. But those aren’t the artists who Douthat references as influential in her work, although she does include the body blueprints made by Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil in the early ’50s.3

Douthat goes back to the 19th century to tap Talbot as first to photograph clothing.4 In 1839, the year generally accepted as the birthdate of photography, he placed lace on “light-sensitive paper thus, anticipating a long history of photographic artists drawn to the imagery of clothing,” Douthat writes in her artist statement.

Well-versed in art and fashion history, Douthat is drawn to “work by other artists who confront memory and loss.” She singles out Christian Boltanski’s installations; Beverly Semmes’ giant dresses of the early 1990s; Petah Coyne’s white wax sculptures; Keith Carter’s 1994 photograph Jessamine’s Gown; Kenda North’s color photographs of dresses from the late 1970s; Irving Penn’s photographs of Issey Miyake clothing; Barbara Kasten’s “Photogenic Paintings”; and Adam Fuss’s photograms of clothing.5

Anita Douthat, Vanishing Act, 1993, Art-in-the-Windows installation in an abandoned theatrical costume shop on Fourth Street, sponsored by C. A. G. E.

In “Under the Sun,” Douthat presents three series involving clothing — “Transparent Uniforms,” 2000-2002, 2007; “Bridal Suite,” 2004, 2007; “Alterations,” 2007 — but she first explored clothing in Vanishing Act, a 1993 Art-in-the-Windows installation in an abandoned theatrical costume shop on Fourth Street; C. A. G. E sponsored it. For it Douthat made photograms of objects she had found in the defunct shop as well as a thrift-store dress that she imagined could have been used in a musical.

Douthat returned to clothing in 2000 with her “Transparent Uniforms,” but this could have been presaged by a series of photograms using metal printing plates from 1950s women’s fashion newspaper ads done at the end of the ’90s.

The “Transparent Uniforms” series was a tribute to her mother and her generation, the 1950s when you left it to Beaver and father knew best. Douthat was thinking about the fashions of the time, those wasp-waisted shirtdresses with bustlines that looked like rocket nosecones, and how they “represent a set of fascinating contradictions. By contemporary standards, these dresses seem rather dowdy, but their transparency is extremely sensual,” notes Douthat. “They serve to remind us of an idealized femininity that we both reject and find strangely appealing. The women who once inhabited them remain with us in our imaginations, but, like all idealizations, they never really existed.”

The image that speaks to me the most is perhaps the simplest: Transparent Uniforms XII, 2007. It’s a sleeveless, body-skimming shift with a diagonal plaid pattern. There is a sheer overlay echoing the shape. The metal zipper stands out, striking an aggressive note. It’s a dress that could have been worn by Jackie Kennedy, and its cousin could have been in my closet.

Douthat had not intended to continue working with apparel, but a gift from the artist Joel Otterson changed her mind. As he was cleaning out his studio prior to moving to Los Angeles, he gave her what she describes as “five somewhat dilapidated wedding dresses that had been hanging in his studio for a decade.”

Douthat couldn’t resist their siren call, and began the “Bridal Suite.” She cut “away the multiple layers of fabric in these dresses in order to achieve the desired degree of translucency and transparency,” she relates. “A strange tension exists between the false modesty of the armor-like layering of the bodices and the transparency of the remaining portions of the garment where layers have been cut away.” Six feet tall but only 20” wide, the frothy concoctions are trapped by their circumstance, possibilities cut off (literally by the frame).

Anita Douthat, Alterations: An Imperfect Symmetry, 2007, photograms, gold-toned printing-out paper, 2 columns, 48” x 20”

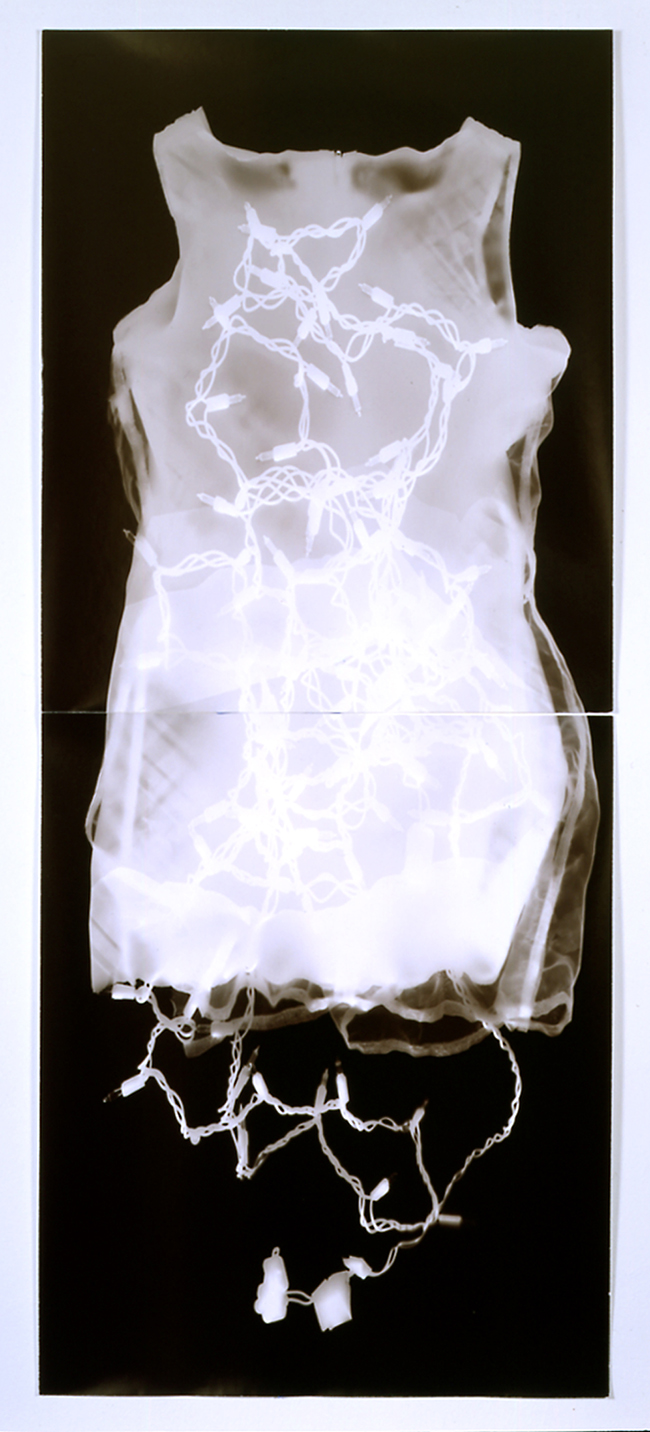

This “tailoring” of the wedding dresses led to another series: “Alterations.” Douthat bought inexpensive dresses at Salvation Army with the intention of altering them drastically, deconstructing them “by cutting and tearing so that other natural and synthetic materials could be exposed through them,” Douthat relates.

When Douthat did her “Transparent Uniforms” in the early 2000s, she was surprised that styles she thought would be dated were back. (Rule of thumb: if you wore it the first time, you can’t the second.) But this time the “deconstructed” look (raw seams, frayed edges, revealed linings, exposed zippers, and perhaps an extra sleeve or two) was coming down the catwalk with fashions from Marc Jacobs, Comme des Garçons, Martin Margiela, Ann Demeulemeester, Yohji Yamamoto, and a lot more copy cats.

(Before you call foul because I’m not labeling Douthat’s photograms as derivative, let me say that this connection seems more like Douthat tapping into the zeitgeist. I’d say fashion designers were making “clothes about clothes” while Douthat uses these alterations to show how women so often must alter themselves to fit society’s expectations. This is seen most clearly in “Wedding Suite.”)

One of Douthat’s more interesting “Alterations” is the diptych An Imperfect Symmetry, 2007. Douthat has laid out a sheer blouse and skirt in two slightly different compositions. The two photograms are hung side-by-side, like paired portraits of the lord and lady of the manor, or maybe the lady and lady of the manor. One “figure” looks ahead while its companion on the right turns to face it. With a large ruffle on the bottom, the skirts are hitched up on opposite sides to create mirror-image curves. They might be curtseying to each other. Douthat arranged the blouses so that their necks are open, and the shapes they form are completely dark. It reads a bit like a head (feel free to go to town about its symbolism).

In some of the “Alterations,” Douthat has added lit fairy lights. (Fuss has done something similar with what appears to be ropes of LED lights.) Conceptually it makes for an interesting play between the natural sunlight that creates the image and the artificial light produced by these strands, but I found them distracting and a little fey.

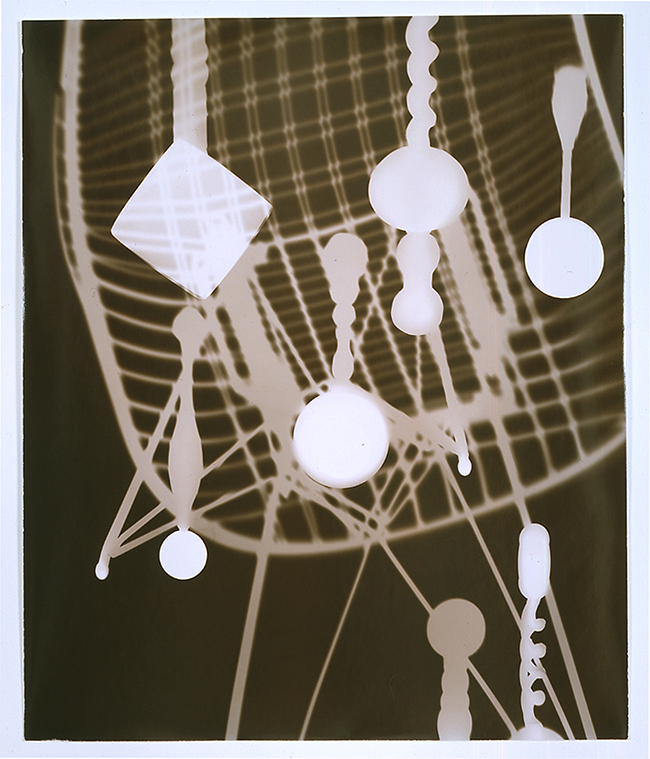

Anita Douthat, Candelabras for Constantin X, 2008, photograms, gold-toned printing-out paper, 48” x 20”

The fourth series is “Candelabras for Constantin (Brancusi).” Douthat explains feeling “drawn to the shapes, I playfully made exposures with these objects, sometimes placing them upright on my paper and sometimes placing them on their sides.” She goes on, “I then added glass objects for their transparent, translucent, and refractive qualities. Something about those shapes reminded me of Brancusi, or possibly the abstract way he photographed his own sculpture.”

I can imagine how much fun Douthat must have had composing these photograms, arranging objects on the printing-out paper, playing with the idea of light represented by the candelabras. She puts her undergrad design studies at Chicago’s Institute of Design6 to good use here.

But there’s nothing distinctive about Douthat’s still-life set-ups. They could have been done close to 100 years ago by the likes of László Moholy-Nagy as well as Man Ray, Alexander Rodchenko, or Christian Schad. Compared to “Transparent Uniforms,” “Bridal Suite,” and “Alterations,” they are, frankly, a little cold. Competent, not compelling.

However, the images of her dresses haunt me still.

Endnotes:

1 Another 19th-century photographic pioneer is Anna Atkins. She used the cyanotype (blueprint) process, placing dried algae on the sensitized paper, to illustrate botanical specimens in great detail for her British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. Considered the first book to use photography, it was published in 1843. She may have also been the first woman to make photographs.

2 Coincidentally printing-out paper, which Douthat uses, stopped being made by Kodak. Chicago Albumen Works was able to import it from France and then England, but that supplier, Kentmere, ceased production in 2009. Douthat had stockpiled enough paper to print in 2009 and 2010 but then she lost her access to a darkroom. However, she continued to make exposures, keeping the paper in a light-tight box until she had access to a darkroom, which she did in the fall of 2013, but “now I have a great darkroom and no access to paper,” Douthat wrote in an e-mail to the author, April 14, 2014.

The range of commercially available photo papers has been diminishing almost from the time it was invented, and it’s going to diminish even more with the advent of digital photography. Cameras using film may be an endangered species. New York City’s B&H photo, one of the biggest purveyors of photographic and video equipment in the world, store offers 16 35-mm. cameras, once the tool of choice for serious photographers. But the number of digital cameras for sale is a staggering 940. So goes film, so goes photo paper.

3 Rauschenberg and Weil were married in 1950, separated in 1952, and divorced in 1953.

4 However, there is evidence that another photographic pioneer, Thomas Wedgwood, son of the ceramist Josiah Wedgwood, made a photogram, what he called “sun prints,” of lace around 1790-1795. But maybe the honor of being the first to photograph clothing should go to Hippolyte Bayard (1807-1887) even if he lagged behind Talbot. Bayard made a cyanotype (blueprint) of a pair of lace gloves, a true article of clothing, c. 1843-1846.

5 It’s easy to add other artists who use clothing. A very incomplete list would include Joseph Beuys’s Felt Suit, Jim Dine’s “Bathrobes,” ceramist Nancy Jurs’ “Armors,” and Elaine Reichek’s knitted garments. But it would be most interesting to compare Karen LaMonte’s cast glass “Dresses,” “Busts,” and “Kimonos” and her monotypes, which she calls “Sartoriotypes” with Douthat’s photograms. Glass has the same qualities of transparency, translucency, and opacity that are found in Douthat’s photograms.

6 The Institute was founded as the New Bauhaus in 1937 by László Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian Constructivist who was well known for his photograms.

Anita Douthat Under the Sun, Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Art Gallery, 650 Walnut St., Cincinnati, OH 45202, www.westonartgallery.com, Through June 8. Tues.-Sat., 10 a. m.-5:30 p. m., Sun., noon-5 p. m. Open late on Procter & Gamble Hall performance evening.