by Danelle Cheney

Comic books firmly straddle the space between visual art and literature. They are unique in format: the visuals are just as important to understanding the story as the words (unlike a traditional book, which may be republished several times with differing sets of illustrations). There are even some which include absolutely no text at all: no narration, no dialogue.

Especially fascinating about comics is the way other mediums appropriate and re-appropriate their plots, settings, characters. We’ve likely all seen a movie based on a comic book series, possibly even a TV show, and quite likely a work of fine art, such as Whaaam! by Roy Lichtenstein. In the early 60s, both Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol found their way to Leo Castelli Gallery, bringing comic book graphics into contemporary art and, with it, the entire idea of pop culture into contemporary art and life.

Superheroes are arguably the most appropriated characters from the world of comics: just scroll through this Wikipedia list of movies based on comics: The Avengers, Batman, Captain America, The Fantastic Four, Ghost Rider, Green Lantern, Hulk, Iron Man, Justice League, Spiderman, Superman, Thor, X-Men, Wonder Woman… and the list goes on.

Also on that list, though, are plenty of movies whose comic book roots seem unlikely, or perhaps we just never stopped to think about them: 300, Alien vs. Predator, Ghost World, The Mask, Men In Black, and Road to Perdition. V for Vendetta and Watchmen certainly capitalized on comic book culture, but how many of us know that Road to Perdition was first a comic? Art imitates art which imitates art.

The Walking Dead is a crowd favorite in television based on the still-current comic series by Robert Kirkman, Tony Moore, and Charlie Adlard, now in its 120th issue. It’s an interesting model for a TV show, with so much existing content and an ongoing momentum through 120 issues and now 40 television episodes; there’s no beginning, middle or end as in a traditional plot. It’s a continually evolving story. Its popularity is unlikely, and has critics and viewers wondering “What next?” Can a comic format be appropriated successfully for television, or will the story eventually fizzle out?

Also worth noting are works in other mediums which explore comic book culture itself. Michael Chabon’s novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay won a Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for its portrayal of the comic book craze beginning after WWII, the big business men behind it, and the confrontation of the sexual identities of his characters as well as notable comic characters (such as Batman and Robin). Following the first season of The Walking Dead, AMC introduced the comic culture reality TV series Comic Book Men. The show is now in its third season and follows the day to day events of a comic store located in New Jersey.

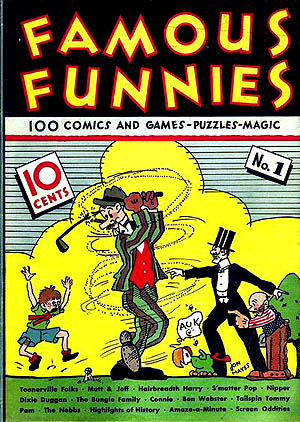

The traditional comic book format was first seen in America in 1933 with the publication of The Famous Funnies. Comic historians generally agree that the first Superman appearance in 1938 (Action Comics #1) began what they refer to as the “Golden Age” of comics, followed by the Silver, Bronze, Copper, and Modern (which we’re presently in) comic ages. While comics are generally considered an American phenomenon, they became (and remain) explosively popular in Japan through the 1940’s and 50’s, pulling influences from the country’s tradition of woodblock-printed booklets from the 18th century. Japanese comics are broadly referred to as manga, which is very popular as a genre in both Europe and the Americas.

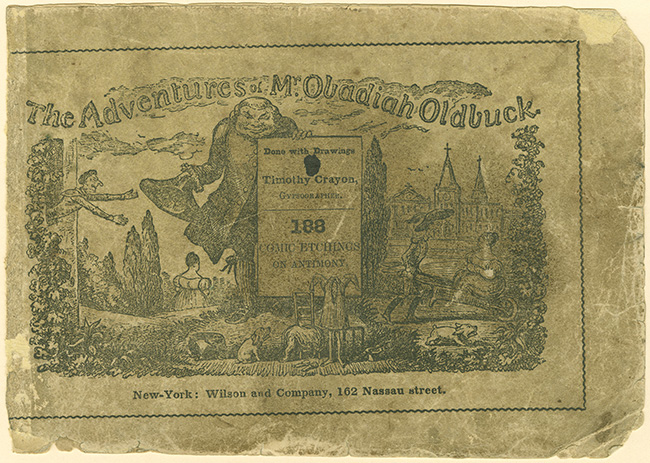

The Adventures of Odabiah Oldbuck, image courtesy of Dartmouth College Libraries Digital Collections

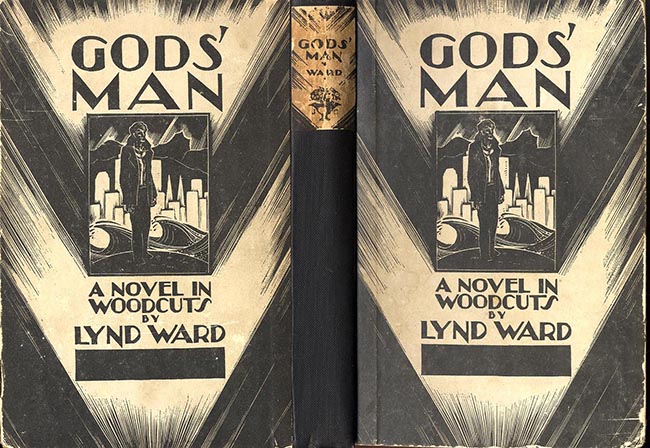

The origins of comic books becomes a little less clear-cut if we employ a broader description of the medium: storytelling interdependent on both words and imagery (and in some cases, dependent on imagery alone). The U.S. publication of The Adventures of Odabiah Oldbuck in 1842 (originally published in Sweden in 1828) is often cited as the precursor to comics as we know them today. Passionate Journey, completed by Frans Masereel in 1919, would later inspire Art Spiegelman to write Maus, the first comic to win a Pulitzer Prize (placing the comic medium squarely in the realm of serious literature). Lynn Ward’s novels in woodcuts in the late 1920’s and 30’s also influenced comic artists after his time. God’s Man by Ward is a particularly stunning example of the medium, pulling inspiration from the Expressionist and Art Deco movements—although Ward’s storytelling uses no words (Which makes us ask: what about cave paintings, then? Illuminated manuscripts and intricate tapestries? Are these comics of sorts? Hmmm.).

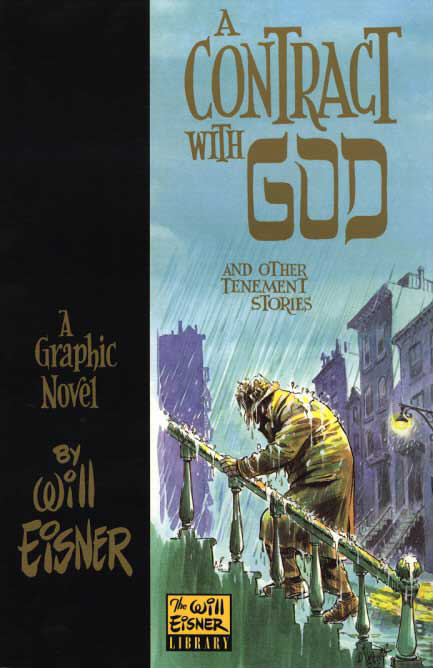

You may have heard the term “graphic novel” used as well; it’s come under fire from artists in the medium for being unnecessarily floofy: “just a marketing term,” as Alan Moore says. Other terms have also been used, such as “comic-strip novel” and “illustrated novel.” Will Eisner popularized “graphic novel” by using it on the cover of A Contract With God, a fantastic set of stories about relatable people in everyday situations. Graphic novel is generally used to differentiate between a set of periodical comics (such as the Superman series), and a self-contained work that reads more like a novel with a beginning, middle, and end (such as Moore’s V for Vendetta and Daniel Clowe’s Ghost World). I might liken them to the difference between a sitcom and a movie; in the end, it’s all video.

Alien, Predator, and Alien vs. Predator are a particularly interesting example (though some might declare “low-brow!”) of the appropriation and re-appropriation between comics and other mediums. Alien the movie was released in 1979, directed by Ridley Scott and enormously popular with both critics and the box office. Eight years later, Predator was released and though not loved by critics at first, eventually made its way onto “best of” lists. Four years later, Dark Horse Comics released a spin-off combination of both films, the Aliens vs. Predator comic series (which continued to be published as recently as 2007), appropriated by the Alien vs. Predator box office hit in 2004 (and Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem): films based on comics based on films.

Comic book culture seems to be experiencing a surge in popularity, perhaps finding a place in the public sight lines instead of just the periphery. The recent explosion of popular superhero films along with TV series such as The Walking Dead and the visibility of Comic-Con may be making comics more “cool” than “nerdy.” The medium holds further potential for work of literary and artistic depth, and we should watch closely to see how other art forms appropriate and re-appropriate comic artists: art imitates art which imitates art and more art.