by Keith Banner

Posh, intelligent and no-nonsense, “Cries in the Night: German Expressionist Prints around World War 1” (June 21, 2014 to August 17, 2014 at the Cincinnati Art Museum) is both a scholarly tour de force and a pleasure just to look at. Curated simply with blocks of necessary wall texts contextualizing and expanding on the art, the show moves through periods of time in Germany and Austria starting with the founding of the Brücke in 1905, and taking off with the Blue Rider group in 1911. “Cries in the Night” travels all the way through World War 1 and finishes with the Weimar Republic era in Berlin, circa 1930. Artists represented in the show include Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Georg Macke, Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, and Otto Dix.

Max Pechstein (German, 1881-1955), Dancer in Mirror, 1923, Color woodcut, Irwin and Judith Hanenson Collection, 09/10.40:6, Copyright through ARS

Wassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944), Three Riders in Red, Blue, and Black from “Klänge”, 1911, color woodcut, Museum Purchase: Anonymous Gift in memory of Helen Pernice, 2014.2, Copyright through ARS

The birth of Expressionism, according to the exhibit, comes from a moment when Impressionism and art in general in Europe is beginning to question the nature of what it means to make at and look at pictures. Printmaking, it turns out, became a fascinating, quick and deliberate way of expressing deep-seated emotions and philosophies that truly are tested and shattered once World War 1 hits in 1914. The avant garde depicted in the selected works of the Brücke (best represented in the show by Emil Nolde and Max Beckman) seem to be working through not just styles but guttural allegiances, creating art that burns away décor and illusions in order to show the world what it means to be canaries in international coalmines. Max Pechstein’s sarcastic and brutally elegant “The Lord’s Prayer” (a portfolio of twelve woodcuts from 1921) confiscates Psalms and repurposes it as a tell-all expose about government mismanagement and societal confusion. The Blue Rider group, symbolized by the whimsical and slightly unnerving abstractions of Wassily Kandinsky, react to the chaos and bureaucratization of chaos of World War 1 by turning inward, charting territories that can’t be found on battleground maps. Kandinsky’s “Small Worlds” (a 1922 portfolio of twelve prints, six lithographs (including two transferred from woodcuts), four drypoints, and two woodcuts) is a triumph of both under- and overstatement. Spinning out a visual language of calligraphic lines and bursts of color, it also is a beautiful example of Bauhaus design. Kandinsky is creating a microcosm and macrocosm here, universes too large to run away from and too small to ignore.

Otto Dix, German (1891-1970). Transport of the Wounded in Houthulster Forest from “War”, 1924, etching, aquatint and drypoint. Gift of Albert P. Strietmann. 1951.138, Copyright through ARS

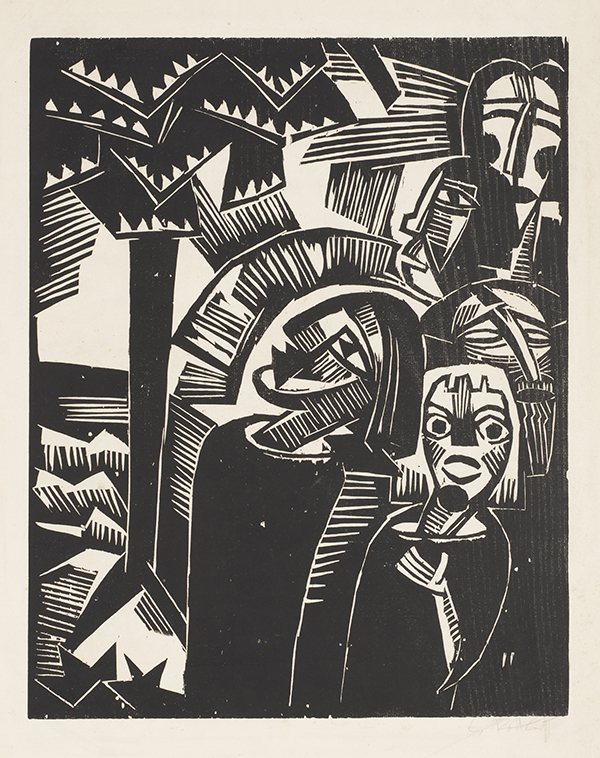

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (German, (1844-1976), Christ Curses the Fig Tree, 1918

woodcut, Mr. and Mrs. Ross W. Sloniker Collection of Twentieth Century Biblical and Religious Prints, 1955.446, Copyright through ARS

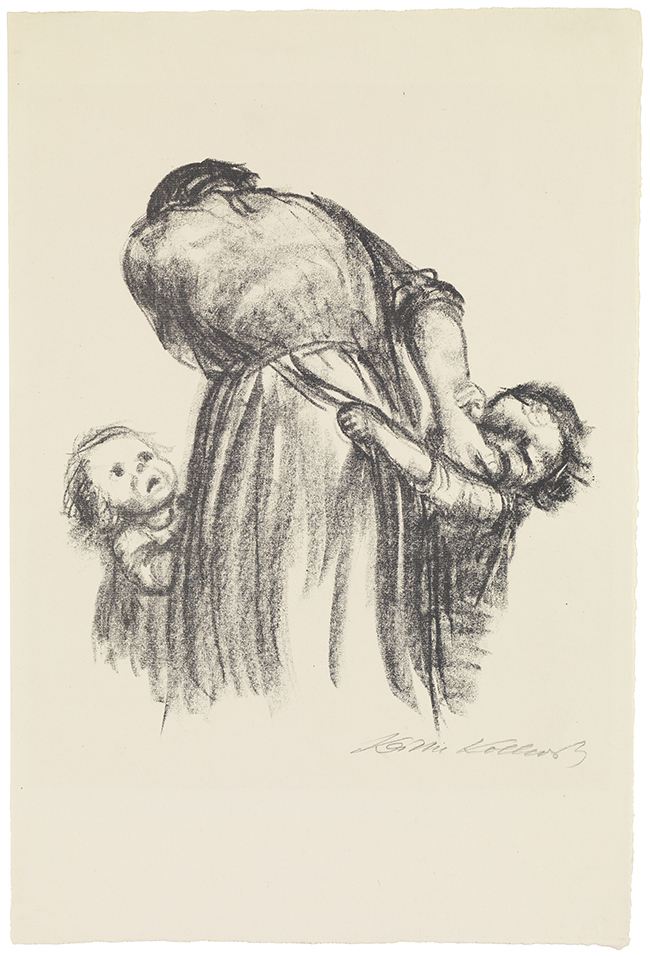

As you walk through “Cries in the Night,” you can feel just by looking at the gorgeous combinations of primitivism and craft that these artists are trying to uncover the secret to editing out what does not matter – the magic lies in the lines and the blurs, the mistakes and intentions gilded into stained-glass logos that ride the line between personal outrage and artistic prayer. All of these artists speak the same aesthetic language and yet the dialects in each print become the way we get to know the era and the concern and the eventual anguish. Käthe Kollwitz’s “Death Grasps at a Group of Children,” a 1934 lithograph, is both sophisticated and ragged, and is the greatest example. Kollwitz figures out through simply depicting a horror that a political cartoon can have the devastating power of a scream, and it’s that screaming that needs to be encased, examined and finally heard.