I was invited to attend the Founder’s Opening of “Beyond Pop: A Tom Wesselmann Retrospective” at the Cincinnati Art Museum, which for me, felt like both a homecoming and a reunion. It was heartwarming to see the hometown museum of one of the greatest masters of Twentieth Century Art celebrate the dedication and achievement of his long and successful career. It also afforded me the all too infrequent opportunity to visit with my old friends, Claire Wesselmann (the late artist’s widow) and Jeffrey Sturges, who were delivering a presentation on Tom’s work and creative process the night of the opening. Although I have a first hand working knowledge of Wesselmann’s process (I was a studio assistant for him from 1988 to 1994), the digital imagery coupled with Claire and Jeff’s anecdotal and casual conversational style of presentation offered an intimately insightful glimpse of the artist I fondly remember. Together, they created for the audience, a genuinely warm and accurate portrait of the man behind the genius, an indefatigable spirit with an insatiable need to create.

It’s interesting to note the show’s title, “Beyond Pop”, because although Tom is forever linked with the Pop Art movement of the 1960’s, the trajectory of his artistic development as revealed in this exhibition shows an artist of exceptional range and scope as well as a tireless determination for invention. He eschewed the Pop label, preferring instead the term “New Realist”. In fact, in his own words from a 1983 journal entry, he states unequivocally, “I consider myself, now and always, a formalist — less concerned about the image and more concerned about how it is formed.” He essentially explored three traditional themes consistent throughout art history, the nude, landscape and still life, and was always searching for innovative ways to push their boundaries. From the earliest collages right up to his last painting, a consistent motif was his use of art historical references within the image. Early on, in The Great American Nude paintings for example, they served as collaged compositional elements as well as an homage to the great masters he revered (Matisse being a favorite). While later, in many of the steel drawings (Monica Sitting with Mondrian Variation No. 4) and cut-out aluminum works (Monica Nude with Cezanne 3D Charcoal and Monica Nude with Lichtenstein (3D) (Artist Version) ), as well as in the “Sunset Nude” paintings (Sunset Nude with Matisse Odalisque), the references are made by the artist’s hand rather than collaged. In doing this, the organic Wesselmann painted figures no longer compete with the rectilinear printed elements but become more lyrical and fully cohesive with them. In these later works, Wesselmann is still regarding the artists whose work he values, but it’s as if the master has at last realized his place among them within the pantheon of Modern Art.

In her discourse with Jeff the night of the opening, Claire related to those in attendance that Tom once told the art historian Marco Livingstone, he knew the work he would be making ten years in the future, but that he had to work in stages to arrive at it. The true value of viewing an artist’s production over the course of nearly a half century compressed into a condensed timeline such as this retrospective, allows for an understanding of how the creative mind really works. As in

life, it is a process of growth, trial and error, working through issues and themes and eventually coming full circle to a deeper and more meaningful understanding. In 1993, Tom began hanging sheets of mylar over the steel drawings and painting the transparent film with acrylic paint. The mylar was then hung next to the work and used as a reference for the actual oil painting. The sheets were then later cut up and tossed out. One day, as the scraps were being collected for

the trash, a certain juxtaposition of overlapping fragments caught Tom’s eye. He began to arrange the scraps on the table and was immediately interested in the seemingly endless possibilities of abstract compositions available to him. These scraps were soon assembled into collages, which led to a new and abstract direction in his work. To quote the artist, “As a student I was so involved with de Kooning’s abstractions, that I realized that I could never make my own

art unless I denied de Kooning as much as I possibly could… My main goal was to make these literal images, nudes, still lives, smokers, landscapes, etc, as exciting as the de Kooning abstracts were to me… But now with my new abstracts, I was excited to find myself back where I wanted to be in 1959, but on my own terms.” The move to abstraction was a wholly fresh approach in that he was constructing compelling and dynamic non-objective paintings from reused gestural scraps of his own previous literal drawings. The process was informing and giving birth to a new process, which reached its crescendo a decade later in Screen Star, the mammoth tour-de-force of three dimensional aluminum shapes writhing in a torrent of flaming color.

Tom Wesselmann (American, b. 1931, d. 2004)

Screen Star, 1999-2003

oil on cut-out aluminum

109 x 139 x 43 in.

Lent by Claire Wesselmann. © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed

by VAGA, New York, NY, Photo Credit: Jeffrey Sturges

The exhibition spans the entire forty five year career of Tom Wesselmann, from 1959 through 2004. When I walked through it the first time, I felt as though it was too small a show… not comprehensive enough. Perhaps that was due to my familiarity with the artist and the vast scope and incremental nuances of his work. But after I’d allowed myself to fully digest the import of its content, decided that it indeed was a nearly perfect encapsulation of an impressive career. All too often, retrospectives include so much imagery and information that, about halfway through, the viewer succumbs to sensory overload and can’t beat a path to the exit fast enough. From the humble, diminutive collages of his early years, through the monumental shaped smoker and still life canvasses, steel drawings and aluminum cut outs, to the heroic-scale Sunset Nude paintings, this show effectively covers all the stages of Wesselmann’s oeuvre without the viewer running the risk of an apoplectic seizure. It’s all there, support material, reference photos, sketches, drawings, maquettes, even the manuscript notebooks containing the country music he composed.

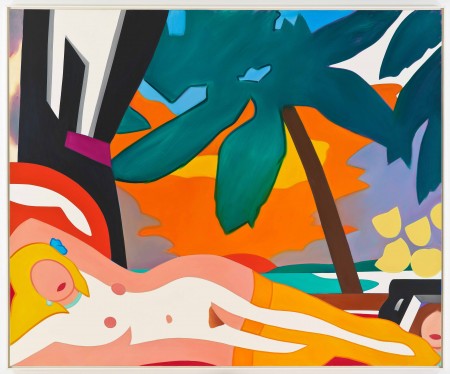

Tom Wesselmann (American, b. 1931, d. 2004)

Sunset Nude With Big Palm Tree, 2004

oil on canvas

105 x 128 in.

Lent by Claire Wesselmann. © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed

by VAGA, New York, NY, Photo Credit: Jeffrey Sturges

The show culminates with the Sunset Nudes, where the entire journey comes full circle. In his final series, Wesselmann returns to painting on canvas and in a sense, to the reclining figures of the Great American Nude from forty years earlier. The paintings are imbued with a rich exuberance; a confidence, satisfaction and joie de vivre that is attained solely from years of dedication and experience. In Sunset Nude with Big Palm Tree, a consolidation of the major thematic elements of Wesselmann’s career come together in brilliant virtuosity. The nude, bedroom, landscape and still life: a half century of exploration spilling out onto the canvas in a palette more explosive than ever before, for no other reason than the sheer joy of painting. All this against the backdrop of a radiant sun setting in the distance. Although Tom was a selfproclaimed formalist, I wonder if he used this motif purely as a design element or if he truly saw these paintings as his swan song? I can’t help but think, he left these last paintings as his final gift as he rode off into that eternal sunset.

At the Cincinnati Art Museum Founder’s Opening reception for “Beyond Pop: A Tom Wesselmann Retrospective”.

From left: Jeffrey Sturges, Claire Wesselmann, Kevin T. Kelly.

–Kevin T. Kelly

This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

This exhibition has been made possible with the sponsorship of Christie’s