Stewart Goldman’s career has shown many variations during more than 50 years of painting and drawing. Through it all, color has driven his art.

Perhaps a bigger force behind his creations, although not always as obvious, have been absences, or memories of things that no longer are. It’s interesting that absence has such a large presence in many of his works and artistic periods because he says he has not experienced major loss in his life.

Goldman has created images both dark and bright. Some of the darkest, and seemingly most realistic, involved the Holocaust, even though he personally had no direct family connection with one of the darkest parts of human history. Still, being Jewish, and having a grandmother arrived in the United States from Russia decades before the Nazis grabbed power, created introspection.

“My grandmother came from outside of Kiev, and came here at the turn of the century, around 1910 or so, I think it was,” he said. She had witnessed anti-Jewish pogroms, which reared up several times in that region’s history.

Some of his works in the 1980s and ‘90s as he reflected on the Holocaust were a twisting of surrealism with seemingly realistic depictions of concentration camps, although many of the works were twisted, topsy-turvy versions of cityscapes from his own experiences, combined with details from death camps he has visited in Europe.

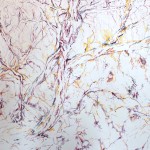

Since 2000 he has continued to mull the Holocaust, but sometimes in different ways: For instance, his Lodz Bridge, created in 2006, used red electric tape that with time and gravity eventually peels from the surface it is “drawn on.” As it deteriorates, the crumbling tape comes to resemble barbed wire.

He often uses pencils to outline where the tape is applied. That way, after the red or blue tape vanishes, and the overall image deteriorates, “the ghost of the image is there,” he said during a recent interview in his Camp Washington studio.

He has used the technique to “draw” large maps of Baghdad; Washington, D.C.; and New Orleans, three cities that have faced their own recent human, political and natural problems and disasters.

In the late 1980s, he created bright images filled with cherubs that were reflections on works by Rubens through a modern eye.

During a long-ago conversation someone suggested that perhaps cherubs were so prevalent in Renaissance artworks because the child-mortality rate was so high. He notes today that it also was very high during the Holocaust. Cherubs are something he repeatedly has revisited.

Once, “I decided I would paint cherub heads,” he said. “And I did that as a Holocaust piece. It’s been shown a few times, along with the portfolio. I painted children and friends, portraits, and then I painted a lot of translations of cherubs from early paintings. They were painted on six-inch squares.

“They were hung high on a wall, above a layer of barbed wire, so there was a separation of the viewer from the work,” he added. “And then played children’s lullabies in the space…. We found a recording of lullabies sung in German, Spanish, French, Russian, Yiddish, Italian…. And they played in the space.”

“And then there were children’s handprints on the wall, under the images,” he said. “Charcoal handprints on the wall. And I thought about it later, I thought it might have been more interesting to have when people come into the space, they could show that they put their handprints on the wall.”

That would have created another emotional bond to the piece, he noted. But, “as it was, it was a little more emotional than I anticipated.”

Several years ago he did another installation using electric tape to depict gas chambers, a guard tower, barracks buildings and other death camp symbols.

Other subjects through time have involved mythology. His latest works, not yet shown, contemplate the story of Daphne from Greek mythology, the freshwater nymph who, fleeing the god Apollo, was transformed into a laurel tree to escape. Based on photographs he shot at a park of thermal springs in New Zealand, sulfur and other elements have painted trees and the ground alike in unexpectedly bright colors.

The works at first may resemble abstract expressionism with blank areas of white interspersed, but instead, his lines are carefully contemplated before they are made. They’re more like drawings with paint.

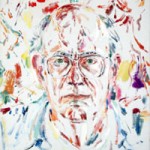

Even some of his self-portraits are painted this way, showing empty patches on his head that are not drawn out, but with his eyes piercing the viewers. No, he says, he does not imagine himself fading away across time as he paints those.

“I’m trying to be as specific with different locations within the form when I’m doing the painting, whether it’s a portrait or something else,” he explained. “I’m interested in how your eye works and moves around a painting.”

For the record, Goldman himself is certainly not fading. He works in his studio as much as ever. In fact, about a year ago, he joined the board of trustees at the Cincinnati Art Museum as its first full-time practicing artist. He also is one of the few regional artists to have had a solo show at the art museum, 2009’s Presence through Absence.

“Boards are made up of people who financially support” the institutions in question, Goldman notes. When former museum Director Aaron Betsky “asked me to join the board I told him I couldn’t make the donation that is expected of the other people who go on.”

But Betsky understood that, picking him based on his merits as a respected longtime artist. Among his awards, Goldman received the Cincinnati Post-Corbett Award as Outstanding Individual Artist in 1988.

Some of his works are in museum collections, including Cincinnati Art Museum and Springfield Museum of Art. Others are in private collections around the world.

Born in Philadelphia in 1936, art “has been something I did, as long as I can remember,” he says. While many future artists doodle in class, he would actually create images of his classes.

“I sometimes got my satisfaction in school from my art experiences, even in science classes, where I could illustrate experiments and events that were happening in classes,” he said. “Long ago observation was important to me.”

During his childhood, Philadelphia had several arts centers that offered free classes, and he took some. He also took classes in art school, before pursing, in two parts, an arts degree at the Philadelphia College of Art (now The University of the Arts). After three years, he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do and didn’t have much money, so he pushed up his draft date and joined the Army. When he returned, the school had added a fine-arts program and he switched to that.

He did abstractions while in school but switched to representation around the last year before his 1962 graduation with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts in painting. The representational work continued after college.

After school he worked and taught painting at an art center in Philadelphia. He moved to Cincinnati in 1968 after accepting a teaching position at the Art Academy when it was in Eden Park.

“I taught painting and drawing when I got here,” he said. “Freshmen and sophomores, first-year and second-year students.” He teaching continued 33 years, before he retired in 2001.

“Teaching never was an interference to doing what I wanted to do. I retired (to paint more), and that was a good thing,” he said.

He veered back toward abstraction after visiting Europe in 1997.

His travels have affected his work, and he seems especially touched by the massive Pergamon Altar that’s the most popular museum attraction in Berlin. The mammoth marble sculpture from the second century BC shows Greek gods and heroes in fierce combat with enemies.

Looking around at all those missing pieces of the battle scenes, “I was interested in the fact that it was like the battle was still going on,” he said. “There were arms missing, heads missing, legs missing.”

Absence can sometimes indicate presence for him.

“And so I started doing, eventually, abstract paintings using parts of the landscapes I’d been working on, but abstracting them,” he said. He became “very conscious changes about the color, and leaving certain areas in the images white, that they were void spaces. In a way, there were things that are missing, in the same way that in the Holocaust there are people who are missing.

“These are something that was in some way driving, still driving, my mindset about the paintings. And so the paintings then had areas in them that were left white,” he said.

Recently he’s been working on what he called minimalistic representations based on photographs he took in that New Zealand thermal park, with its references to Daphne, and areas of white.

“Color has always been a driving force in my work,” he said. “I brought those photographs back, and started working from them, in my contrary way, I went to a very minimalistic painting.”

Rather than saturating a canvas with color, he says he’s working with a process more similar to drawing with paint on largely white surfaces.

“I’m still doing those,” he said.

He’s married to Kristi Nelson, an art historian by training and currently the interim dean of Arts and Sciences at the University of Cincinnati. She was senior vice provost and will return to the provost’s office before the year ends.

He is a father of two: a daughter is a lawyer in Brooklyn, and a son is involved in education in Germany.

- Stewart Goldman in his Studio, Copyright 2014 by Mike Rutledge.

- Stewart Goldman Self Portrait, 1998.

- Lodz Bridge, 2000.

- Lodz Bridge, 2001 (note the tape is peeling away).

- The Visitor, 1970s.

- Goldman in his Studio, Copyright 2014 by Mike Rutledge.

“I basically see all the work that I do as in some way autobiographical,” he said. “Even though these are abstract paintings I’m doing it from things I’ve seen and places I’ve traveled to. The rooms that I did earlier were about where I lived. The Holocaust was about something to do with my identity, my past history, family history, religious history. It’s always part of it. So everything had something to do with where I was, what I was thinking. And it was a question of finding a form to do it.”

Like Picasso, Goldman believes artists should not shoehorn their careers into a specific style. Instead, their styles must evolve to match the subject and meaning, and their own growth.

In the late ‘90s he was invited to a small fellowship for a month outside Munich. His work there shifted to abstraction from figuration. While there he helped establish a student-exchange between the Art Academy and an art school in Munich, one of Cincinnati’s sister cities. The program faded when the instructor in Germany retired.

There are no missing pieces in his painting efforts.

“I’m here every day,” he said about the studio where he has painted about 24 years. “I’m not here on the weekend. Sometimes I come in, but not too often. I’m here during the week. And the paintings go very slow. The older I get, the slower they go. The paintings I’m doing now are taking a little more time in terms of the decision-making, just because of how clean I want them to be. But I’m here five days.”

He laughed when asked if painting is something that gives him pleasure or is something he must do. “It’s a combination of both,” he said. “I like being here.”

–Mike Rutledge