Stationed inside the Cincinnati Public Library’s downtown branch, in the International Fiction alcove, is an archipelago of funky institutional wooden tables topped with glass rectangular boxes. Inside the glass boxes are 55 illustrations by three artists depicting the cities Italo Calvino poetically maps in Invisible Cities, the shapely novel/epic-poem/dialogue that has an effortlessly epic quality to it, a grandeur that somehow sculpts itself into an intimacy through the course of 160 pages or so. Published in 1972, the book is both a cosmological treatise on what everything cultural and civilized means or doesn’t mean, as well as a very meticulously detailed encyclopedia of metropolitan metaphysics and desire, all filtered through an ethereal back-and-forth between Marco Polo and Kabla Khan.

What may sound pretentious as hell is not, though. Calvino’s instinct is to get out before you know what’s hit you, and each little section of the book detailing the names of imagined cities, and what each city looks like and how it is lived, has all the peripherals burned off, yielding sleek revelatory poetry and narrative, each set-piece defined and invented from thin air like a magic trick that slowly metamorphoses into continents and creation itself.

Illustrating such a lofty literary accomplishment would seem pretty daunting, but the artists in “Seeing Calvino,” Leighton Connor, Matt Kish, and Joe Kuth, do as the Master did: there’s effortless grace and precision on display in that International Fiction section, each depiction not nailing down Calvino’s vision as much as crocheting it into a kind of fan-boy intimacy that makes you want to reread the ur-text all over again, this time with visions in your head outside of the words that caused the visions in the first place.

The hand-made, doodle-like simplicity and innocence involved in each drawing (all of them done on the same sized paper) allows the show itself to transform from fanzine into psychological geography and fairytale, as if each illustration depicts several other stories outside of Invisible Cities while also concretizing each place like a new attraction at Calvinoland (as opposed to Disneyland). There’s minimalist grandeur here, all kinds of little diamonds in the rough, codes and moments like cave paintings or secrets Paul Klee whispered to himself. A folk-art obsessiveness informs the aesthetic of each artist, and yet their singular lines and compositions kind of sideline the “folk-art” aspect in favor of an astute, glorious amateurishness on purpose, repurposing Calvino’s initial intentions for the book.

In fact, after seeing “Seeing Calvino,” you start to think that maybe the Italian genius was simply just trying to relocate paradise in a sketchbook, Utopia in a doodle. Each illustration relocates Calvino’s gaze, showing us a vision as close up as a microscope in a dream and as far away as a satellite in another galaxy, all of it conveyed in ink, crayon, paint, collage, giving off an overall effect of a scrapbook supercharged into myth, each artist forming his own visual language to get at what language can’t do: pictographs and iconography forming into postage stamps and snapshots, commemorating a land and sea and space so invisible they burn into unforgettable.

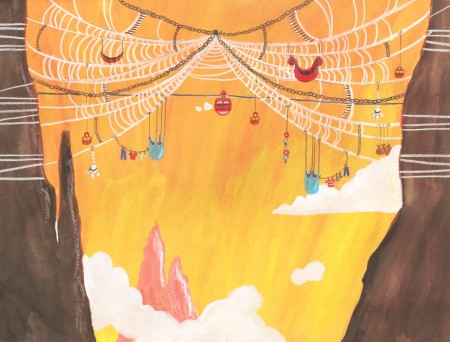

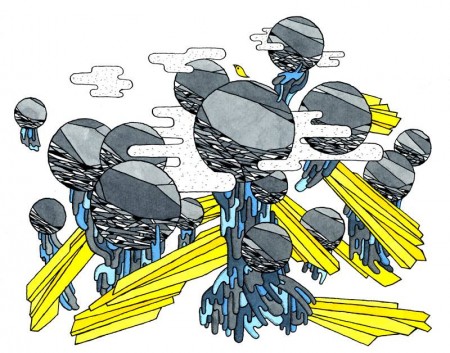

One of the best pieces in Seeing Calvino is Kish’s “Diomira.” It takes Calvino’s poetic instructions and produces a rat-tat-tat combo of clouds, shards, and globes that anxiously mimics art-deco without giving into its solemnness, an architecture losing its sense of structure while solidifying into symbol. Connor’s “Euphemia” accesses a thought-bubble to reconfigure how a city can lose itself in its own myths and legends; unlike the other two artists Connor seems more intent on locating Calvino’s narrative in mid-flux, creating an intimate tableau. And Kuth’s “Octavia” has a Dr. Seuss lyricism laced with an R. Crumb cringe, with its kinky orange sky and whipped-cream clouds framing brown mountains laced with bridges and ladders. In the book, Calvino describes Octavia as “the spider-web city… Suspended over the abyss, the life of Octavia’s inhabitants is less uncertain than in other cities. They know the net will last only so long.”

One of the best exhibits happening right now in the city, Seeing Calvino creates its own web of meanings and tropes from a grandly conceived book stockpiled with magical moments and mysteries. The drawings the three artists have made don’t nail down Calvino’s vision as much as provide a net connecting their visions and the writer’s. This concatenation of nations and states somehow feels sublimely down to earth without losing its sense of beautifully articulated whimsy.

–Keith Banner