Carl Solway (and family) have been so deeply entwined with the art gallery scene in Cincinnati that it takes a timeline on the wall to keep it all straight. He graduated from Walnut Hills in 1952; ten years later, he opened Flair Gallery at Fifth and Race. Ten years after that, he had two galleries in Cincinnati. By the early 70s, he was part of a venture to bring Midwestern artists to East Coast eyes with some shared gallery space on Spring Street in Manhattan. Though he has gradually retrenched his exhibition venues, by his fiftieth anniversary in the business, Solway’s galleries had shown more than 800 artists. The Art Museum is celebrating some of the range of Solway’s contributions to Cincinnati’s art scene with a show, jointly curated by Kristin Spangenberg and Matt Distel, of about 50 works designed to give us a sense of Solway’s taste, ambitions, connoisseurship, vision, and salesmanship.

The curatorial choices are restricted to works that have entered the Museum’s permanent collection as the result of direct purchases from Solway’s galleries or as gifts from the gallery or the family or the many Cincinnati collectors Solway has cultivated over the decades. In terms of evaluating an exhibition, these are some rather substantial restrictions. In truth, it is a show about museology and patronage, about chance and choice, which are in themselves very interesting things. It is a shame that the exhibition doesn’t tell us more about the shows that formed the original contexts for these works. One has come to expect better from an art museum when it comes to the many ways that art can be contextualized. But despite being a rather tight curation of Solway’s own rather expansive curation, the show is driven by an important proposition: What did the art world look like to a strong-minded gallerist who spent the greater part of a substantial career not in New York, combining art scholarship and commerce, seeking out and—surprisingly often–helping to make works of art and an appetite for them in his home town?

Though the exhibition, as far as I could tell, is not chronologically arranged either in terms of when works were made or when they entered the CAM collection, it tries to give a feel for what we might call the Solway Moment. What was it like to open an art gallery in 1962? While great examples of classic modernism were readily available from abroad, in America, Abstract Expressionism was on the wane. It could be argued that Abstract Expressionism was, aside from Pop, the last moment when American art could be felt to speak with one voice, even if we can now know how many other competing voices were hoping to be heard. A perfect manifestation of post-war culture, Abstract Expressionism was muscular, triumphalist, exuberant, urban, alcoholic, misogynistic, and—too often–depressive and suicidal. These are a lot of notes to sacrifice in constructing a vision of the art scene, but Solway was more interested in what was going to come next. As the exhibition quotes him as saying, “I decided to focus on the classical work of my own generation. All the really great art dealers of the past are those who fought for artists of their own generation.”

By and large, he took a pass on the lyrical abstraction that followed, though through him a very fine Helen Frankenthaler painting, “Rock Pond,” entered the collection, as did Sam Gilliam’s “Arch” (1971). Gilliam is an artist to whom Solway seems to have paid a good deal of attention, and who has taken me a fair amount of time to warm up to. I would have loved to have seen the whole show from which this work came (something that struck me more than once in looking through the exhibition), but I thought it really looked great in the context of this show. “Arch” is a painting on the edge of sculpture, and suggests one of the directions painting might go in when it gives up the privilege of having been made on an easel. It is also a reminder that Solway often supported artists with an idea and an experimental edge.

Solway was interested in a few artists whose work resonated with the powerful echoes (or aftershocks) of Abstract Expressionism. The show includes three of the several hundred sketches Robert Motherwell made in just a few weeks in 1968 in response to Alban Berg’s “Lyric Suite.” They served as a reminder that one thread of Abstract Expressionism was the apparent effortlessness of composition, though it crossed my mind that in general, Solway’s taste tends not to run towards apparent effortlessness. The three sketches are deliciously loose and pay homage to the improvisatory energy of American abstraction, though I wondered whether improvisatory was also a muse to which Solway tended not to respond to. The show also included a large scale de Kooning lithograph, “Love to Wakako” (1970), as his work tended more and more to straddle abstraction and figurative. (It is interesting that in general, Solway tended to steer clear of conventional figurative work—indeed, he seemed to have steered clear of most conventional representational genres, including landscape and still life.) The de Kooning features broad, ghostly brush strokes that are practically objects in themselves, a look to which the exhibition returns in the Lichtenstein print.

Solway’s interest in abstraction tended more towards the scholarly. The Museum owns a complete set of Kandinsky’s “Kleine Welten” (“Small Worlds”–1922), a suite of a dozen woodcuts, lithographs, and drypoints that Solway had picked up on an early trip to Europe. Models of classic European elegance (three words that do not describe the typical Solway work), the prints are austere and Bauhaus-y, and together, they constitute an anthology of intricate and tightly thought-out ways that pictorial space and represented space resemble and comment on each other. In both title and contents, the prints are literally microcosms, and form the chronological foundation for Solway’s career-long interest in ways that artists abbreviate and miniaturize space. It is not a very large conceptual step from Kandinsky’s small worlds to more contemporary abstract maps, including Buckminster Fuller’s “Dymaxion Air-Ocean World Map” (1980) and Nancy Graves’s series of “Lithographs Based on Geologic Maps of Lunar Orbiter and Apollo Landing Sites” (1972)—both works that Solway published as well as exhibited. The Graves work is composed of brightly-colored dots, but is in some ways the opposite of Pointillism: the further back you get, the less it resolves into shapes and forms. It is the post-modern map, where the parts do not readily subordinate themselves to a whole. In retrospect, the Graves prints suggest a vision of topography as a computer might understand it, without requiring the sugar-coating of the illusion of terrain. These prints are part of a long-term interest Solway had in works that had fresh takes on one of modernism’s most central issues—how art represents a multi-dimensional world in, typically, two dimensions, though it’s interesting to note how many of the objects in the show in one way and another blur the border between 2-D and 3-D.

Solway made a substantial imaginative investment in Pop, and saw ways that its visual vocabulary resonated well after its height in the 1960s. He seemed to have been drawn to the work of artists who absorbed some of the best that Pop could teach, and took it another place. Though there is a perfectly acceptable Wesselmann nude in the show, I thought the Lichtenstein “Sower” (1985) was more remarkable, bought from a show in 1986 where the artist, like de Kooning before him, was exploring the brush stroke itself as object. Starting with Van Gogh’s homage to Millet, the print enlarges elements of a familiar painting to heroic proportions. Solway seems to have been drawn to the painterly edge of Pop. Where Pop was relentlessly flat, this print, which is a photolithograph with elements of photo screenprint and woodcut, is dense and layered. Even more dense and layered is Frank Stella’s “Estoril Five 1” (1982). A relief printed etching and woodcut on prepared, hand-made paper, it has interesting points of connection with works like Jasper Johns’s number paintings, where images are stacked upon each other helping to create a lush sense of depth and dimension.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Solway organized the Urban Walls project to put paintings up on bare walls throughout the city and place art before the eyes of the public. Today, only one remains, though since then, many other urban walls have been painted by many other teams of Cincinnati artists. Urban Walls got further than Solway’s 1972 proposed project with Claes Oldenburg, which would have set a mammoth bar of Ivory soap afloat at Cincinnati to drift down the Ohio to the Mississippi and out to the Gulf, dissolving as it went. There is a “Let’s just do it” quality to Solway’s art activities. He has made money for himself and for a number of now-famous artists before they became famous (a substantial proportion of the works in the show were published, sponsored, organized, or fabricated by Solway), but in addition to being a dealer, he should rightly be considered a facilitator, collaborator, patron, and civic benefactor. It is harder to be equally enthusiastic about another of Solway’s Pop-oriented projects, the Andy Warhol portrait of Pete Rose (1985). This screenprinted painting of one damaged commodity as constructed by late Warhol, already himself a damaged commodity and commodifier, seems a testimony to the aridity of Pop as it faded in its role as a cultural driver. (Compare how much more interesting the late works of Johns, Lichtenstein, Dine, and Rauschenberg have proved to be.) It also seems a reminder that portraiture was generally not the muse that spoke most persuasively to Solway. And though Solway intensely pursued anything he felt was truly unique to Cincinnati, the Rose portrait seems like the work of an outsider looking in, and not very attentively at that. Warhol is someone who has heard of Cincinnati on the news but has never seen, understood, or tried to capture it. (Isn’t it that place where the river caught fire?)

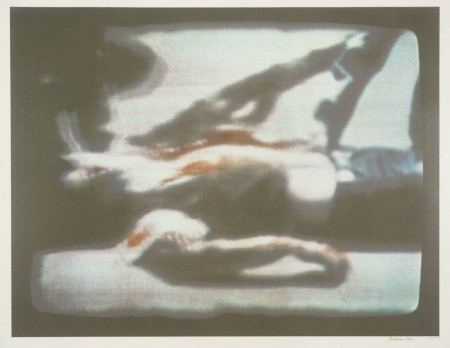

Works that have included Pop-inflected photography are much more successful. (I missed in the Museum’s show more acknowledgment of Solway’s success in presenting shows of straight-up photographs, though perhaps these works have yet to end up in the permanent collection.) In the context of this show, I was freshly struck by the linkages between Pop’s imbedded critique of the domestic economy and Sandy Skoglund’s strange and serene household nightmares. One of her excellent works, “The Green House” (1990), shows a living room and its occupants overwhelmed by objects and images, in this case, dogs in green and indigo, and furniture that seems to be reverting to the wild. Richard Hamilton is the British artist whose 1956 collage “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” was accidentally responsible for the initial adoption of the word “Pop” as part of an art movement (a muscle builder pauses, carrying a huge lollipop). The famous Hamilton collage helped set Pop’s tone by suggesting that you need look no further than the ordinary living room to see the destruction of our imaginative autonomy at the hands of consumer-driven capitalism. Hamilton’s photo screenprint “Kent State” (1970) captures a powerful moment in the content and technique of art. The image is taken directly from a camera photograph of a television image of one of the students shot during the 1970 campus demonstration. The technique calls attention to our under-acknowledged massive and constant importation of imagery into our lives, never knowing when one might actually make a difference. It might even be fair to say that there is something map-like in the image; it is a radical, transformative abbreviation, a translation of a four-dimensional reality into a two-dimensional image. The student’s jeans are blue and his blood is red. The rest of the colors are muted and indistinct; in 1970 television, color had still not emerged fully victorious over black and white, and the print seems partly to be enacting this transition, with strong political overtones. An image of a body lying on the ground is a powerful way to take advantage of the horizontal bias of the televised image. The picture reminds us that we are capable of knowing a stupendous amount about the world, but are condemned to know it in a second hand way, our hearts and minds responding to images of images. This was a central part of Pop’s message, and it seems a central part of what Solway came to believe in as he searched out artists who trafficked in images that can be both familiar and arresting.

Solway is particularly well-known for his advocacy of pioneering video artist Nam June Paik who is represented in this show by one of his robot-like creatures made up of old cathode-ray tv sets—in this case, manufactured by Cincinnati television figure Powell Crosley, Jr. (There is also an intriguing suite of prints by Paik, including a wonderfully playful piece of planets.) Jenny Burman, in the May 17 Cincinnati Magazine, says that Solway “fabricated and sold more than 200 sculptures made of television sets.” It’s hard not to think that this would have made a terrific story in itself, one I wish the Museum show had shared in greater detail. I have to confess that I have never really warmed to Paik’s anthropomorphic settings for his video sculptural collages; there is something about the tone of these hulking Robby the Robots that doesn’t make sense to me. In the context of this show, however, the video content of the piece looked very impressive. Paik’s video loops are not ruminative. As a barrage of flickering, transitory images, they seem to capture both the urgency and the emptiness of television. It clamors for our attention, has relatively little that it actually tells us, but achieves a kind of beauty of its own in the process. I found myself more taken with Alan Rath’s video installation “Litter” (1992-94). Five small television screens are scattered around a bamboo framework. (Are we to think of political prisoners in tiger cages?) Far more austere than Paik’s piece, “Litter” has images of the fragmented human body (another map?): there are two eyes, two hands, one mouth. This adds up to an interesting sense of what we are constituted: we see, we act (and feel), we speak, all within an airy but confining superstructure.

Though Rath’s online biography lists himself as a citizen of San Francisco, he was born in Cincinnati. Early in his career, he was shown at the CAC and one of his first commercial exhibitions was with Solway. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, there was talk about whether there was a “Cincinnati School” of artists, one that might be compared, say, with the “Chicago School.” One doesn’t hear much about that these days (or, for that matter, of the term “regionalism” altogether) and I doubt that it’s much missed. But considering his genuine and career-long interest in promoting art in Cincinnati, it would have been nice to get a clearer vision of Solway’s relationship to Cincinnati artists. One artist with strong local connections is Kentucky-born Jay Bolotin, represented in this show by a large cast-paper multiple “The Circular Nature of Enoch’s Dilemma” (2009), a work related to his recent mythographical project, “The Book of Only Enoch.” “The Circular Nature” features rats as they trudge around the border of an outsized playing card or a board game (another map?). They are winding their ways among tree trunks, unless the tree trunks are also pieces in the game. Though far less loquacious than many of Bolotin’s works, this one has his signature figures that skirt the boundary between two and three dimensions, a print on the edge of sculpture. More loquacious, perhaps, is Cincinnati-born Jim Dine’s lithograph “Cincinnati II” (1969), a beautiful piece printed in pale purple ink on black consisting solely of the names that trace his connections to family and friends in his home town. Louise Dine, Leo Guttman, Belle Cohen, Bernie Katz, Red-Head Eunice: it’s midway between the place cards at a large family wedding and the overheard feverish whispers at a class reunion. As a collection, the names are ghostly graffiti, an elegiac cataloguing of an artist’s past.

An outlier of solemn beauty, Rafael Ferrer’s “Umiak/Whale” (1972) is a hanging sculpture that was shown at the artist’s solo installation at the CAC in 1973, and has been in the Solway’s personal collection ever since until it was given to the Art Museum. A sculpture made of pieces of rawhide, it looms, only vaguely whale-like, suspended from the ceiling. Its shape is held together by a kind of a wooden spine with one crossbar. Its surface allows some mottled light to come through, the natural texture of the materials giving it some of the elegance of an abstract painting. It is a little less mediated than many of the other Solway pieces and speaks well of the range of feelings and tastes brought together in this collection. Steve Rosen, in the May 18 CityBeat, says that the Ferrer piece “once hung over the Solway’s dining table.” This is a wonderful note, and helps to personalize the show, helping us envision museum-worthy art in the setting of an actual home. I feel that the exhibition would have been improved by suggesting any of a variety of contexts for the art in it. More information about the actual exhibits from which the works originally came would have been one obvious way. I would have happily settled for a glimpse behind all the decisions that led to these fifty works being shown now at the Museum. There are curatorial decisions, of course, both in arranging this show and prior to them, when the pieces were acquired. But there were also decisions that could have focused more on the tastes and budgets of individual collectors, and how Solway appealed to them and educated them. For a show that is centered on the years of professional work performed by a strong personality, it would have been a good thing if we could have gotten a clearer sense of some of the components of that personality.