A taut crimson thread inscribes a tension between two forms, not so much seen as felt. It wraps around a smooth basalt stone on the gallery’s floor, extending some feet up to a suspended form, a spectral lattice, like a 3D-printed tumbleweed, defined less by its appearance than its lightness and upward gesture — like a pocket of warm breath pushing through a film of soap on a summer day. Yet the stone’s weight thwarts this momentum. There’s a pleasurable tension at play here, erotic even: The crimson thread locks these two forms on the cusp of la petite morte.

There are more basalt rocks, crimsons threads, and rising lattice forms in various stages of decoupling in “Breaking Point” (2019), the eponymous work in Margaret Smithers-Crump’s solo exhibition at Houston’s Rudolph Blume Fine Art/Artscan Gallery. Works here explore such cusps and tensions, irruptions of rhizome entities sprawling along walls and through space. To encounter these entities is to encounter some kind of spooky-action-at-a-distance ASMR.

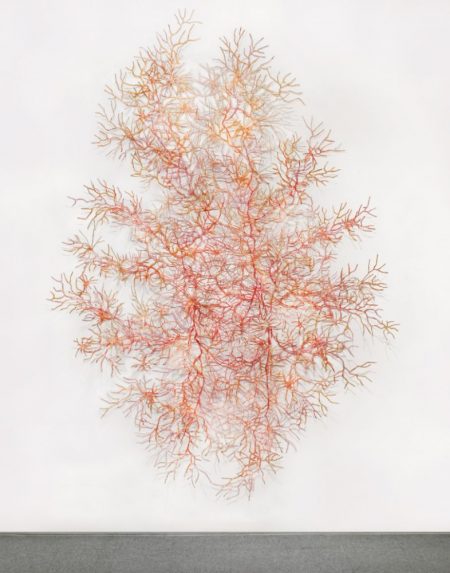

Nearly all 17 works involve reclaimed polymethyl methacrylate, better known by the trademarks Plexiglas and Lucite. It’s striking to see such organic structures rendered in a material associated with the slick, the cool, the manufactured. Coral-like forms branch outward, teeming and clustering in discrete loci. I wonder if they’re sentient? “Kinship Network” (2018) is a 9-foot structure that grows out of the wall. Painted in shades of red, it reads as veins or roots — nerve endings shooting off from twining cords.

I’m reminded of the chimeras in Alex Garland’s 2018 film Annihilation (adapted from Jeff VanderMeer’s spectacular novel). The film takes place in Area X, a kind of Ur-space inhabited by a mysterious information-refracting force, a strange mechanism through which encountering lifeforms rewrite one another’s genetic code. In its most memorable scene, scientist Josie (Tessa Thompson) walks into a glade. Through the eyes of Lena (Natalie Portman), we see her transform into a flowering bush, eerily retaining the shape of her human form. The scene is infused with a subversive beauty that ushers in a Lovecraftian strangeness, which is similar to the way the work operates here.

Smithers-Crump’s artist statement appropriately frames her work in ecological terms. On this footing, the exhibition succeeds: The work here is ecological, which is different from saying it deals with the ecological. Rather than depicting or telling us about dying coral reefs or burning Amazon forests, the artist explores something of their underlying essence, or the essence of how we experience them. Its aesthetics operate on the tensions, the imbalances, the slow motion catastrophe of the Anthropocene. The anxiety of living in an age of mass extinction, when we’re barely gesturing towards an appropriate global “oh shit.”[1] She accomplishes this by placing delicate bodies in relation to each other, re-presenting as alien something so familiar as to be invisible: the vastness, the complexity, the fragility of the ecosystems we inhabit.

The forms here feel more like collections of bodies, systems unto themselves. A system of systems. Too often, art works invoking the systemic mirror the coolness of hard science. The warmth here is a refreshing change. The sensitive manner in which they have been cut, painted, assembled, and arranged in space is seductive. I already mentioned these works are erotic: they excite, they are felt with and in the body. Here is an erotics of the Anthropocene. Enthralled with this work, I’m aware of synapses firing in my brain; of my own microbiome and its porousness to the external world. Electrochemical signals traveling through nerves resembling the forms I’m looking at. Dopamine rush. Neurochemistry altered.

In “In Silence” (2015-2016) three forms like lace tornados hang over a wooden boat in the center of a reflective black pool. The boat is just smaller than human scale, evoking simultaneously an artificial distance and a feeling of enlargement. That shift in scale in turn invokes the oneiric: this is a trauma dream[2] of the Anthropocene. Looking into the pool’s surface, the inverted reflection of conical forms amplifies a sense of dreamlike alterity. A doubled, darkened world looks back from beneath the glossy surface. The lighting is arranged in such a way that, peering down, I see no trace of myself. There’s only darkness.

–Steve Kemple

Margaret Smithers-Crump’s Breaking Point runs through October 26th at Rudolph Blume Fine Art / Artscan Gallery (1836 Richmond Ave., Houston TX 77098).

[1] cf. Greta Thunberg: “I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act.” (“‘Our house is on fire’: Greta Thunberg, 16, urges leaders to act on climate.” The Guardian, 25 Jan 2019)

[2] See Timothy Morton’s book Being Ecological (London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2018) for a discussion of “ecological PTSD.” I thought about this book a lot while writing this review.