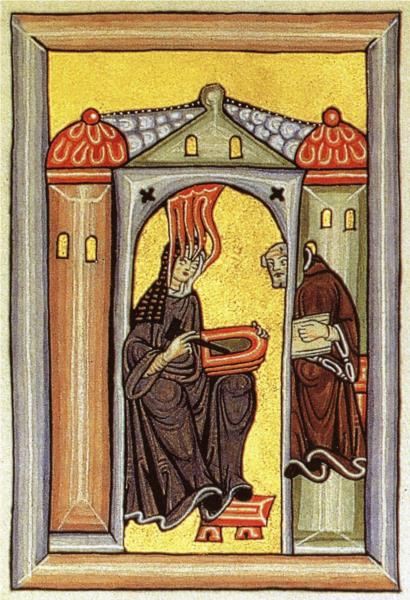

This first image shows Hildegarde receiving Divine Inspiration and sharing it with the monk Volmar. She was famous throughout central Europe in the late Middle Ages, advisor to kings; venerable abbess, composer and musician, artist and mystic. She is called the ‘Sibyl of the Rhine.’ Hildegard of Bingen was as Sir Roger Penrose is to the twentieth-twenty-first century, she the polymath of the twelfth century.

Hildegarde came into my world via a graduate course in Women in the Arts. She was one of the only luminaries of the Middle Ages we discussed and remains so vivid in my mind I vowed to visit Bingen if I ever had the opportunity. Musicians know and love her. Her beautiful manuscript illuminations are lesser known to some extent although the most well known of her illuminations were made for her visionary work called Scivias. Pope Eugene III granted papal approval to the writings, and authorized Hildegard to publish everything she received in visions. If she were alive today, she would be a major ‘intellectual influencer.’

I choose Hildegarde of Bingen to spotlight for this issue of Aeqai focusing on women artists because Hildegarde was a woman of such undeniable magnitude and vision. Her manuscript illuminations shimmer with mystical and sensual energy. The colors and compositions are magnificent. Artists of the Middle Ages belonged to guilds and were not that often known individually. It wasn’t until the cusp of the Renaissance that individual artists such as Giotto became better known specifically. While we can go back to ancient Greece which celebrated individual artists whose names we know – Phidias, Praxiteles, Pollykleitos, mostly sculptors – by the time of Rome’s usurpation of Mediterranean power and thus creativity, the individuality of artists declined. Trained Greek artists were hired to make copies of Greek sculptural masterpieces the Romans so admired. Roman creativity tilted toward the military and the arenas of engineering and architecture – aqueducts and the Coliseum in Rome. They couldn’t create the shimmering marble visions like Nike of Samothrace presently at the Louvre or Aphrodite of Knidos, a copy of which is at Hadrian’s Villa near Tivoli in Italy.

So how did Hildegarde arise after centuries of unknown artists-in-craft-guilds? Certainly choosing a monastic life provided her with the unbridled opportunity to express her visions, her intellect and her creativity. Most other women of talent such as painter Judith Leyster who was in the same artists’ guild as Rembrandt, fell into obscurity once they married and had children. This explains why scholar Linda Nochlin wrote a 1971 essay that rocked the contemporary art world: “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” It is considered a pioneering essay for feminist art history and art theory. Nochlin studied and pointed to the societal suppression of women so Hildegarde, in entering and then leading a monastery in the Middle Ages, naturally took on a leadership role and could guide her own destiny.

Hildegard of Bingen was born in1098 in Disibodenberg, Germany, the tenth child of a knight. Apparently it was the custom to devote her life to the Catholic Church and she entered the convent either as an older child or a young teenager. At a very early age Saint Hildegard had begun experiencing regular holy visions that continued throughout her lifetime. In addition to being a nun with mystical and prophetic insights, she was a true pre-Renaissance polymath: political and social moralist, musical composer, poet, naturalist, herbalist, gemologist, author of medicinal and botanical texts, and playwright. She even penned the earliest morality play. By the mid-12th century she was serving as the mother superior of the Benedictine monastery she had founded at Rupertsberg on the banks of the Rhine River. Incredibly she lived to be 81.

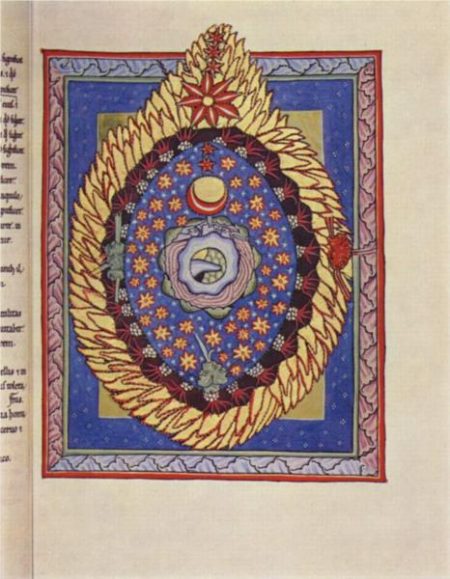

The Universe is Hildegard’s most celebrated manuscript illumination. I am struck first by the fact that the almond shape of her Universe image is a mandorla, from the Italian for ‘almond.’ This almond shape represents the Virgin Mary in some manuscripts and wall carvings and ultimately it is the shape of the vagina. Versions of this almond/vagina are seen throughout Medieval Europe, for example. This does not take away from the originality of Hildegarde’s design of the Universe. Rather, it is a very shocking and bold shape to use. In the hands of other artists of the time, predominantly male, their universe is a flat disk or a circle or globe. Hildegarde’s outer edge of her Universe image is fringed with yellow fire and it fairly undulates or quivers. It is very erotic to my mind. At the center of the manuscript is a tiny organic protrusion that also is very female. Art historians dance around the graphic and organic nature of this image and I found no direct descriptions by others such as I am providing and alluding to. This is easy to interpret as a highly charged erotic vision of the universe created by a great Creatrix. Obviously, in her time, Hildegarde was an ardent Catholic so this interpretation is based on a more Jungian interpretation of image and content.

Immediately I think of Judy Chicago and surmise Chicago was acquainted with Hildegarde’s mystic illuminations. Chicago honed in on centralized imagery as specifically feminist, so Hildegarde of Bingen’s Universe is a perfect model of such practice.

I made a special pilgrimage to Bingen in search of Hildegarde in1991 while I was in Europe teaching abroad. She was and still is a lodestar to me. I was raised Catholic so her illuminations were revelatory to me and fit within a framework of my education and artistic grounding. Visiting her ancestral home was meaningful and at that time all educational materials on Hildegard were very simple and sincere. There is, however, nothing simple about the surviving manuscripts (and copies) she and her nuns created which are in collections. From Wikipedia: “Hildegard’s works include three great volumes of visionary theology; [a variety of musical compositions for use in liturgy, as well as the musical morality play Ordo Virtutum; one of the largest bodies of letters (nearly 400) to survive from the Middle Ages, addressed to correspondents ranging from popes to emperors to abbots and abbesses, and including records of many of the sermons she preached in the 1160s and 1170s; two volumes of material on natural medicine and cures; an invented language called the Lingua ignota (“unknown language”); and various minor works, including a gospel commentary and two works of hagiography.

Several manuscripts of her works were produced during her lifetime, including her first major work, the illustrated Scivias (regretfully lost since 1945); the Dendermonde Codex, which contains one version of her musical works; and the Ghent manuscript, which was the first fair-copy made for editing of her final theological work, the Liber Divinorum Operum. At the end of her life, and probably under her initial guidance, all of her works were edited and gathered into the single Riesenkodex manuscript. Her contributions were of such high value that copies of works were made of the millennium to ensure survival of her corpus.

Last October, Christ Church Cathedral in downtown Cincinnati featured St. Hildegard von Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum (which she wrote around 1151 for performance by the cloistered nuns in her abbey.) It is a sacred drama featuring the struggle for a human soul between the Virtues and the Devil. Although performances of this work are extremely rare, here I was attending and listening to this haunting musical performance staged by Collegium’s Cincinnati on a balmy October Sunday, with vision of Hildegarde’s shimmering illuminations floating in my mind above the magnificent singers.

–Cynthia Kukla

May 25th, 2020at 12:33 pm(#)

Thanks Cyn,

Wonderful article & great info.

Love the images of her work…

I visited the wiki H of B web page. Most AMAZING woman!

An inspiration!

Brandy Danu

May 25th, 2020at 1:21 pm(#)

Awesome article. Very informative and insightful. Thanks for sharing.

Cynthia L. Koshalek