“Filling the Void” by Rick Mallette at the Summit Hotel Gallery is an agoraphobic’s nightmare. The aptly titled show perfectly describes the vast and spartan 5700 square foot gallery space, met by ambitiously scaled artwork that attempts to tackle that vastness with claustrophobic forms, blazing colors, and palpable energy. The artist presents twenty-three abstract paintings and large-scale drawings made between 2020-21, and one work on paper from 2004 that measures 7 feet high by 40 feet long.

Summit Gallery Installation View

Photo by Susan Byrnes

That piece, “Blue Mural”, presides over the back of the gallery with an ethereal blue, black and white palette, occupying the viewer’s entire visual field. Rendered in a cartoonish graphic style, hundreds of distinct shapes are defined by bold black outlines with white highlights, suggestive of biological forms but wholly invented. There is a repetition of dynamic motifs, such as tubes, folded layers, jagged lightning bolts, clouds, and water droplets intermittent throughout. The forms seem to interact with each other; fluids and gasses are being expelled and exchanged, and physical forces are implied by radiating lines and arcs, thirsty black holes and clutching cavities.

Blue Mural (detail), 2004, Ink and acrylic on paper, 84 x 480 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

With its elongated dimension and quasi-hieroglyphic forms, “Blue Mural” implies a quirky narrative. The artist has described the content of his work as “emotional caricature”, a phrase that reminds me of the opening scene of David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel “Infinite Jest”, when the lexically gifted Hal Incandenza meets with a college admission committee, defending his intelligence despite slipping grades. He makes an elegant and impassioned plea for the committee’s understanding, but they watch in horror as he actually expresses himself with incomprehensible grunts, gurgles, animal-like groans, and “waggling”, flailing limbs. If one could translate Hal’s monologue into its own visual language, with its prolific and fluent yet unrecognizable sounds, its disconnect between brain and tongue, in all its awkward gestures and guttural sputters, the result would be “Blue Mural”. The piece mirrors the brain’s neuronal workings, its dendrites and axons seeking connection, its synapses firing in every direction, with speed and agility. Its language is incompatible with ours, its message unintelligible to us.

Mallette’s practice is rooted in drawing, in part informed by the idea of “automatic drawing”, a technique employed by Surrealist artists as they attempted to tap into the dreamlike, illogical imagery of the subconscious. Drawing is critical to this technique because it is the fastest, most direct conduit to record the pre-conscious imagery that arises. This way of working is making divorced from thinking, something many people have experienced when they make “doodles” in the margins of a notebook or while on hold on the telephone. Mallette elevates the doodle to the level of art, both in form and process. Seeing the drawings of Basil Wolverton in Mad Magazine as a kid particularly influenced his own fluid graphic style, as well as the graffiti-based murals of the late Keith Haring.

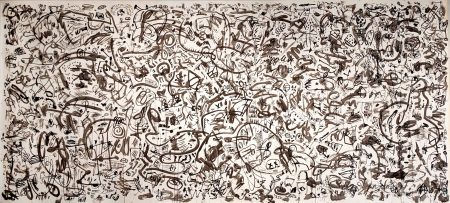

Outdrawn, 2021, India ink and acrylic marker on paper, 108 x 240 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

Drawing also enables Mallette to incorporate the freedom and inherent structure of improvisation into his work. Similar to a jazz musician, he practices, prepares his equipment (acrylic markers, paint, ink, etc.), enters the stage (paper or canvas), and plays. No resulting work is ever exactly the same, and in these pieces, there is no predetermined plan and no revisions or corrections – what’s created through the ephemeral process is the artifact of direct experience, and that’s the point. In his statement he said that even after twenty years of working this way, when he starts a new piece “there is still an element of fear”. “Outdrawn” is both drawing and performance in this sense. With a 9 x 20 ft. piece of paper, and black acrylic marker and India ink, his objective is total improvisation within a period of concentrated energy. He incorporates a specific speed into his strokes of ink and marker and uses music to set the pace. The final piece has two layers, one of hard-edged graphic geometries and biomorphic shapes, integrated with a softer, calligraphic treatment done with strokes of a brush dipped in a less intense black ink. The slightly different blacks give it a subtle depth. The heroic scale and brushwork give it a more delicate, lyrical quality than Mallette’s other works in the show, reflecting the influence of Abstract Expressionist action painting on the artist’s process.

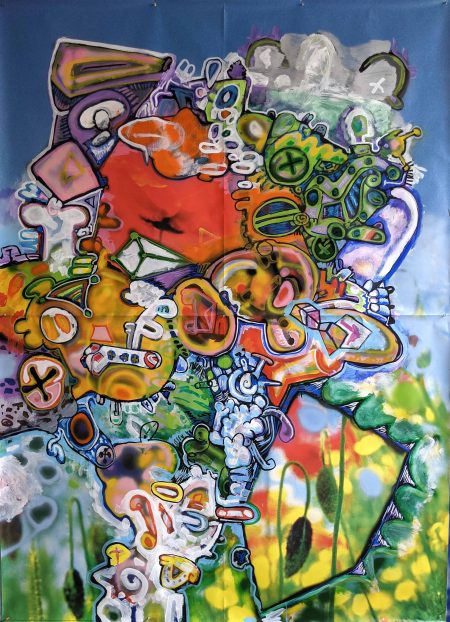

Poppies #1, 2021, acrylic spray and acrylic marker on photomural, 100 x 72 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

Poppies #7, 2021, acrylic spray and acrylic marker on photomural, 100 x 72 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

His acrylic paintings, however, are often reworked, significantly refined from a more immediate, raw state. In the series of five paintings titled Poppies (#1, 2, 5,6, and 7) Mallette also departs from the tabula rasa of the blank page to fill. Here he makes pieces that interact with a photomural of poppies as the substrate. Each painting, made with acrylic spray paint and marker, incorporates elements of the photo, primarily the iconic poppy red and cyan sky. From there the compositions mutate in response to each other and details of the painting’s ground. As the series progresses, the forms become simpler and more defined, from an initial chaotic bundle to eccentric anthropomorphic characters posing in a pastoral tableau.

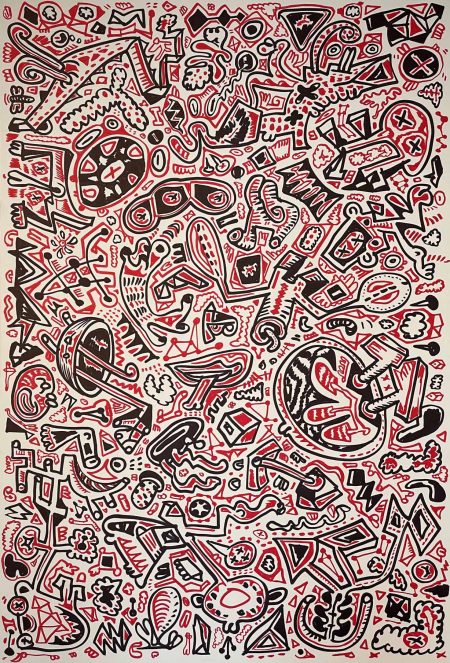

Red, Black Drawing, 2021, Sharpie on canvas, 72 x 48 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

Mallette’s explicit scribblings teasingly suggest but rigorously resist interpretation. The closest he will get to an explanation in his artist statement is “searching for a place where conscious and subconscious meet”, which by definition is mysterious and psychologically charged terrain. His proliferating visual forms attest to his commitment and ability to unearth a continuous stream of unfamiliar imagery; the performative, improvisational works prioritize the act of “searching” at the edge of conscious awareness. If the work “means” anything, we can see it in the very context in which the work is presented: the void is infinite, as is the unending compulsion to fill it. The fear of empty space, known as horror vacui, was a term adopted by the movement Art Brut that championed and emulated creations of institutionalized artists like the criminally insane Adolph Wolfli. The work is characterized by obsessive compulsive images compact with fine details extending to the very edges of the composition, filling in all available space, with little distinction between figure and ground. Mallette shares these compositional tendencies, as seen in “Outdrawn” and in the 72 x 48” piece “Red, Black Drawing”, with its bouncy anthropomorphic forms rendered in red and black Sharpie marker crowding the entire surface of the canvas. Little clouds, hashmarks, and triangles squeeze into every other space.

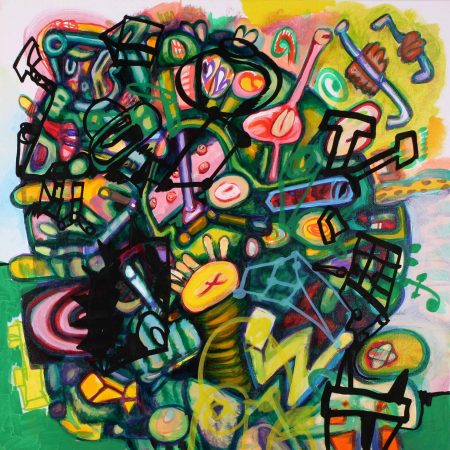

Embers (Man on Fire), 2021, Acrylic on wood, 24 x 24 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

Wet Lettuce Mansplained, 2020, Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 24 inches

Photo courtesy of the artist

Sixteen small paintings occupy another wall. They’re hung very close together in semi-salon style. Grouped together they seem all of a piece, and in fact they were all painted between 2020-21. Within the confines of each canvas, we see the same kinds of graphic forms developed in “Blue Mural”, “Outdrawn”, and “Red, Black Drawing”, but these have a much broader spectrum of colors and are reworked with layers of paint. The titles of the paintings allude to both portraiture and landscape spaces, and compositional conventions such as horizon lines and distant skies set the stage for Mallette’s massing, writhing, undecipherable code. In “Embers (Man on Fire)”, a background landscape space with a central horizon line separates the umber ground from a deep orange sky. The foreground explodes with color: pink, yellow, purple, blue, orange, green. Connected dots, tubes, spirals, targets, boxes, and clouds are intertwined and rendered as flat or dimensional shapes. This mass of forms pushes out toward the sides and top, leaving the background visible, but densely convenes at the bottom edge, grounding the mass and reinforcing the notion of a portrait of a human figure that the title suggests. Similarly, “Purple Ear, Sloppy Science” repeats the treatment of the figure but leaves a white void for the background. In “Wet Lettuce Mansplained”, the small, massed forms take on a rounder, head-like shape against a traditional background space. These paintings play upon portrait and landscape genres to reference the figure and its environment in a state of chaos. The chaos is colorful and playful, but it’s still chaos. To see it depicted is fascinating or possibly revolting, and the brain’s default is to try to make some sense, some order there.

This artist’s work shines in this specific site because it illustrates something beyond the imagery itself, something that illuminates the very impulse for making this work. The tension between the giant emptiness of the Summit’s white cube and the teeming, unfathomable contents that Mallette provides makes for a rare viewing experience; we witness something primal, something that ultimately defines the purpose of all art – the power of a human mark to confront the abyss.

–Susan Byrnes