by Danelle Cheney

Graphic designers are taught to confront and reconcile the relationship between form and content. Is one more important than the other, or equally so? Does personal expression, emotion, and humanity have a place in design, or should designers focus on legibility, clarity, and unity of content?

The first Bauhaus manifesto states:

“Together, let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”

Most graphic design programs today (both bachelors and technical degree programs) focus on modernist principles. Postmodernism, structuralism, poststructuralism, and several other “isms” are taught, but not necessarily as “working models” designers should emulate. Modernism champions the pure legibility of the message; modernist design is minimal and logical.

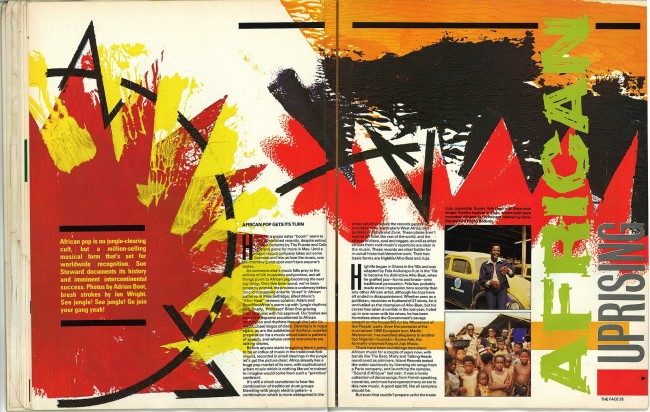

Postmodernism champions personal expression, creativity and humanity. Postmodernist designers use form to express content in a more emotional, intuitive and personal way; legibility can be sacrificed for the sake of human presence and expression. Editorial design in the 1980’s was a particularly wonderful playground for postmodern designers, and still serves as a rich resource for students looking past modernism today. Some of the most notable designers of that time period had little to zero formal training—which makes perfect sense—relying instead on their instincts and intuition to create covers, headlines, and page layouts.

Neville Brody began his education with fine arts courses, and wondered why an emotive, “painterly approach” could not also be applied to graphic design. He received a graphics degree from the London College of Printing, where he agitated his professors by experimenting in ways they deemed unfit for the commercial world of design (including designing a postage stamp with the Queen’s head turned sideways). Brody became well-known as a designer during his time as Art Director at The Face magazine (first published in 1980) for his page designs layered with meaning and expressive forms. Despite having no formal typesetting or type design training, he created geometric typefaces specifically for the magazine (some of his font designs can be seen here), which have been consistently copied and imitated.

Futurism, Constructivism and the Dadaists (as we discussed recently here) clearly all had a major influence on Brody’s work. Brody says “what I drew from [these movements] was threefold: the idea of challenge, of breaking down established orders, the idea of the importance of movement, dynamism, change, and the idea—it was almost a slogan for me then—of ‘putting man back into the picture’.”

David Carson worked as Art Director for the publication Transworld Skateboarding beginning in 1984, giving the magazine a distinctive look with so-called “dirty” or “grunge” typography. Carson, like Brody, received no formal typographic training, and focused on dynamic compositions that he called “subjective, personal, and very self-indulgent.” He rejected conventional typographic treatments, focusing instead on the expressive power of the content to draw inspiration for page designs. As Carson achieved a level of notoriety in the design industry, he was both praised as an inspiration for young designers and decried by others who felt his work devolved too far into chaos. Carson remains active in the design field today and has staked the claim to being the “most Googled” designer on record.

Carson’s designs may be both literal and emotional interpretations of the subject matter, such as this example from his time as Art Director for Beach Culture magazine in the early 1990’s. He interpreted the title “Hanging at Carmine Street” as an invitation to literally “hang” some type from the top of the spread, while composing the rest of the spread in a relaxed, informal manner.

As all designers will be at some point in their career, Carson was confronted from time to time with subject matter that he found—shall we say—boring. One such example was a feature on Bryan Ferry in Ray Gun magazine, which Carson ultimately typeset in Zapf Dingbats to illustrate what he felt was the uselessness of the content (to be fair, it was also typeset legibly in the back of the issue for those interested in reading).

Contemporary art magazine ArtForum—perhaps one of the best known publications in the industry—also appealed to postmodern tastes during the 1980’s with Ingrid Sischy at the helm as Editor-In-Chief. Sischy used page layouts as not only an emotive tool but one for social commentary, particularly during the AIDS epidemic. Expressive, slanted pink type created effective and striking compositions.

During the same time period, Emigre Graphics began publishing a graphic design magazine—Emigre—helmed by designer and editor Rudy Vanderlans. Intended as a platform for his and his colleague’s unpublished works and creative contributions from others. An early adopter of digital design, Emigre gained a reputation for experimental page designs and subject matter while demonstrating what was possible with the emerging technology of desktop publishing.

In an article published in Emigre #18, designers Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum discuss their project intended to bring humanity back to the typeset page: a typeface that randomly regenerates its outline within certain predefined limits of legibility. The result is a page that relates more closely to the print work of Gutenberg, whose work changed from impression to impression—a celebration of both technology and the human hand involved in the crafting of the work, as well as a commentary on the pitfalls of perfected technology. More images of Emigre can be found here, and they are definitely worth a look. The magazine was last published in 2005, but a few copies of different issues can still be ordered online.

The opposing views of modernism and postmodernism (and the artistic movements that inform them) still have relevant voices in the world of graphic design. Designers find themselves debating the philosophies of these movements—some more intensely than others, myself included—and I can’t help but wonder if there is a time and a place for both approaches in design. Just as the world is not distinctly black or white, one way or the other, neither is graphic design.

For more reading on how modernism and postmodernism relate to graphic design and the world we live in, Natalia Ilyin’s Chasing the Perfect is highly recommended. To see more examples of postmodern design, visit David Carson’s website, Ed Fella’s website, and Charles S. Anderson’s website.